Edna Mayne Hull was van Vogt's first wife, from 1939 until her untimely death in 1975. She is credited with writing 12 works of fiction that appeared in Astounding Science Fiction and Unknown Worlds magazines in the early 1940s:

| "The Flight That Failed" | 1942 | (aka "Rebirth: Earth") |

| "The Ultimate Wish" | 1943 | |

| "Abdication" | 1943 | (aka "The Invisibility Gambit") |

| "Competition" | 1943 | |

| "The Wishes We Make" | 1943 | |

| "The Patient" | 1943 | |

| "The Wellwisher" | 1943 | |

| "The Debt" | 1943 | |

| "The Contract" | 1944 | |

| The Winged Man | 1944 | |

| "Enter the Professor" | 1945 | |

| "Bankruptcy Proceedings" | 1946 |

Most of these stories appeared in book form as the following:

| Out of the Unknown | 1948 | (contains stories by both authors; aka The Sea Thing) |

| Planets for Sale | 1954 | (some editions credit van Vogt as co-author or sole author) |

| The Winged Man | 1966 | (revised by van Vogt and credited as co-author) |

In van Vogt's various interviews and articles — in other words, everything intended to be made public — he consistently presents Hull as the author of these tales. Yet these stories bear the hallmarks of van Vogt's own writing, and over the years many have believed that he either wrote them with Hull or did them all himself. (Aside from the similar styles and ideas, sometimes even the same "stunts" were pulled; for example, in van Vogt's Slan and Hull's "The Invisibility Gambit" the story is turned on its head by revealing a major character's full name in the last line.) As a result the authorship of these stories has been in dispute for long time, and it seemed as if the issue would never be cleared up satisfactorily.

Up until fairly recently I firmly believed that she created these works (perhaps with input from van Vogt as an editor of sorts) and I did all I could to put emphasis on Hull as a distinct and separate author. For a while I even purposefully ignored or explained away any information to the contrary. (See below for more on this.) But after prolonged research and careful consideration of the problem I am forced to admit that van Vogt himself wrote these stories. There is daunting evidence that he employed his wife's name as a pseudonym, then found himself more or less stuck with this arrangement. And once on this track he decided to let it remain that way even after his wife's death. His reasons for doing this in the first place will be discussed in depth, as well as various theories as to why he continued it.

Before I get into any of that, though, I'd like to clear up a few points. It is obvious that for whatever reason van Vogt wished for his wife to continue receiving credit for the stories published under her name. (He even gives anecdotes on Edna's inspirations for specific stories in his 1975 autobiography Reflections of A.E. van Vogt and elsewhere, and I'll be saying more on this further on.) So I have tried to strike something of a middle ground on the matter, giving credit to Hull while also presenting the evidence that van Vogt wrote these stories himself. I would also like to make it absolutely clear that my intent is not to defame van Vogt as a wicked-hearted arch-deceiver. At worst I explain away his public statements on the matter as white lies necessary to maintain a writer's "professional secret," a secret which he may have accidentally let slip when he handed over Campbell's letters for Perry Chapdelaine's project without first reviewing them for content (see van Vogt's 1980 interview with Robert Weinberg for more details).

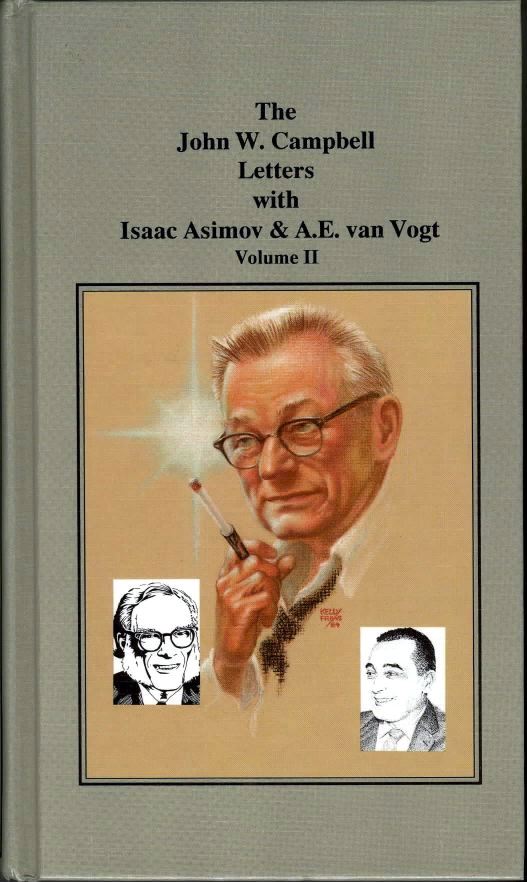

It is this very correspondence between van Vogt and Campbell, as published in The John W. Campbell Letters: Volume II (edited by Perry Chapdelaine and published by AC Projects in 1993) that offers the strongest evidence that van Vogt was the author of the Hull stories. These letters have been in print for well over a decade now, yet they are by no means easily available — with only 300 copies made, the volume is difficult to find and rather expensive. [Update, December 2011: Fortunately, a digital Kindle edition — albeit a very badly formatted one — is now available for a mere $3.95.] And yet as invaluable as these letters are, we are hindered by the fact that while many from Campbell to van Vogt survive and have been published, very few from van Vogt to Campbell from any year are known to exist, and none at all from the 1940s. Both sides of these interchanges would have cast far more light on this matter, but what is available is far from ambiguous. This evidence, though short in length, is crystal clear.

A letter from Campbell to van Vogt dated September 10th, 1941 mentions that Astounding was switching to a larger format with increased wordage, and that Heinlein was considering decreasing his output or retiring altogether (he ended up only cutting back on production). Campbell therefore asked van Vogt for more material to help fill out Astounding and Unknown, and offers the suggestion that he could begin using a pen-name for some of his work — as far as I know it was a universal practice that a single author could not be credited for more than one story per issue of a magazine, and Campbell's magazines were no exception. Therefore pseudonyms were often employed to allow an author to circumvent this rule in an acceptable fashion. Robert A. Heinlein was one such author, publishing a fair amount of material as Anson MacDonald — Anson being his middle name.

Evidently van Vogt took him up on this offer for about a year later in a letter dated August 24th, 1942 Campbell says:

"We'll use the pen-name Dean M. Hull on your stuff. I have in mind running, probably in the December issue, "The Flight That Failed" under that name."

A single highly important fact in the quote above often goes unnoticed: that Campbell, and not van Vogt, at least initially chose which stories would appear under the Hull pen-name. This emphasizes even more than there was no real difference between these stories in the eyes of either Campbell or van Vogt himself, that no specific stories were set aside as needing the Hull byline. All were interchangeable.

In earlier versions of this essay, I assumed that van Vogt had invented this pen-name himself. I have since learned that it was Campbell who usually created these names for his authors (such as Anson MacDonald for Heinlein). I previously tried to explain this pseudonym as van Vogt emulating Campbell's style of pen-name — now it seems likely that rather than the name's use being inspired by Campbell, Campbell himself may very well have created it. Campbell wrote many of his most famous stories under the name Don A. Stuart, a masculine version of his wife's maiden name, Donna Stuart. Similarly, Campbell may have masculinized the maiden name of van Vogt's wife to create van Vogt's pen-name. It's also worth speculating here that "Edna" may have been changed into the masculine "Dean" by switching the letters around. Anagrams have long been one of the most popular methods for creating pseudonyms.

But however interesting it may be, the Dean name is a side issue since before the story appeared it was decided to go instead with "E.M. Hull." This new name matched his wife's initials perfectly while making the "E." gender- neutral. The reason for the change from "Dean" to "E." is unknown — this is one instance where van Vogt's letters to Campbell would have proved invaluable. So in the first proposed form of this pseudonym Edna herself was not credited, and the name was in all likelihood simply modeled on Campbell's "Don A. Stuart."

The first Hull story appeared in the December 1942 issue as planned. This issue also contained van Vogt's "The Weapon Shop." This marked the beginning of his most productive period — the 26 months from December 1942 until January 1946 would see no fewer than 17 of his works appear in the pages of Astounding and Unknown. Also during this period 11 of the tales credited to Hull appeared, out of a total number of 12. It is no coincidence that the greatest number of stories ever to appear by both authors occurred in the same two-year time frame; rather than it being the most prolific period of two individuals, it was the same individual producing both sets. Another interesting consideration is that later on van Vogt explained that Edna lost interest in writing due to her involvement with Dianetics — this happened exactly when it seemed that van Vogt himself had lost interest in writing due to involvement with Dianetics.

At the height of van Vogt's productive output it seemed that yet another pen-name might be needed. In a letter dated August 4th, 1943 Campbell says:

"If Alfred Forrester becomes necessary, he will appear. Sorry in some ways that you didn't think of that one sooner; that E.M. Hull suffers from the difficulty that an E.M. Hull wrote, 'The Shiek' -- an item I'd completely forgotten 'til a reader inquired. But E.M. Hull is now tagged as the writer of the Artur Blord stories."

Alfred Forrester was either going to be an additional pen-name (perhaps to allow three of his stories to appear in a single issue), or it was meant as a replacement for the Hull pseudonym — the evidence is not conclusive and can be interpreted either way, though the first explanation seems the more likely. Campbell seems merely to be lamenting that they didn't think of that name first, rather than seriously suggesting they replace Hull with Forrester. Also apparent here is Campbell's clear belief that these were not collaborative works at all, just as his own Don A. Stuart tales were not.

The Shiek appeared in 1919 and the author's full name was Edith Maude Hull. Many still confuse van Vogt's wife with her, and even today this novel sometimes appears in bibliographies of Hull's works. Fortunately, now that more is known of Edna, the situation is very clear cut: there is no possibility she could have written The Shiek, as aside from any other consideration she would have been about 14 years old at the time!

The last story to appear with the "E.M. Hull" byline was "The Patient" in November 1943, three months after Campbell's letter. It was only out of sheer necessity that the ambiguous "M." was replaced with the more explicit "Mayne" to differentiate the name from the famous novelist's. If it were not for this unforeseen coincidence, in all likelihood it would have remained just "E.M. Hull."

Like Dean M. Hull, the Forrester name was never used but it is likewise worth examining. A.E. van Vogt's first name was Alfred and his Dutch surname means "of the forrester," so Alfred Forrester is a different "version" of his own name. This is another "derivative" pen-name, making the Dean/Edna anagram theory even more likely. It is also worth noting here that Campbell says "Sorry in some ways that you didn't think of that one sooner." This could mean either van Vogt thought of only this name, or he thought up both, so is unhelpful in clearing up the point of who came up with the Hull name.

So what happened to Alfred Forrester? Quite simply he just wasn't needed. There were two reasons for this. Van Vogt's level of output remained high for just a few months longer — in 1944 it dropped to almost half of what he produced in 1943, returning to his 1942 level. Also, even if van Vogt did come to regret using his wife's name he was prevented from switching to a new one, since two series were already established under the Hull name — the Artur Blord and Wish stories. All sequel tales had to be by the same "author."

In a letter from Campbell dated June 9th, 1943 a possible further reason why van Vogt stuck with the Hull name can be inferred. Campbell emphasizes that an author's name should consistently present a certain style of story and that for a change of pace the author should writer under a different name. This rationale could certainly apply (to an extent) to the Hull stories which were by and large more character-driven than van Vogt's usual fare — featuring more interactions and intrigue between individuals — while still being set against the same kind of super-SF or fantasy background in his typical stories. The Wish stories in particular seem geared more towards women than men, both in the theme and in how they are presented. Also, he has been noted as one of the earliest SF authors to put emphasis on capable women in his stories, as opposed to damsels in distress (discussed more fully in van Vogt's 1980 interview with Robert Weinberg). This attitude, coupled with having written "confession" stories from a woman's point of view and for a female audience for almost a decade during the 1930s, no doubt helped maintain the unique flavor of the E. Mayne Hull tales. So, for him, it was perhaps fortuitous that he was forced to make "E.M. Hull" a woman so he could explore this approach more openly.

(An interesting side note: In June 9th, 1943 letter Campbell also said:

"[...] I'd suggest that you try handling stories of the period not more than 50 years hence, concerning mainly the exploration and colonization [...] of the planets. [...] Your previous stories have all been long-range stuff; I very genuinely want to have much greater emphasis on 1945-95 now, and it would be an opportunity for you to change style and treatment in a major way."

I, for one, am immensely grateful that van Vogt never took up this suggestion.)

A desire to guage readers' reaction to his writing may have played a role in his wishes to continue giving Hull credit for writing these stories. Stephen King, for instance, published various works under the name Richard Bachman. This was done partly as a way of seeing how people would judge his work on its own merit when it was not released under his real name, to do away with all preconceptions and expectations that the King name engenered. Van Vogt may have done the same with some of his own work, such as The Winged Man which is the only non-series Hull story to appear in an issue where a story did not also appear under van Vogt's own name. On the other hand, it was not uncommon for the contents of issues to be shuffled around even at the last minute, and it may have been originally slated for the same issue as The Changeling the previous month, or the issue featuring "Juggernaut" three months later. We'll never know for sure.

This could also explain why he retained the pseudonym in all subsequent printings of the Hull tales. In his autobiography, Reflections of A.E. van Vogt, (p. 75) he seemed particularly amused that readers would tell him:

"I enjoy your stuff, Mr. van Vogt; but the stories of yours that I really like are the ones you wrote with E. Mayne Hull."

It was no doubt very encouraging to him to have his work praised without them knowing it, to win approval from a "blind taste-test" of sorts.

(One could of course theorize that The Winged Man was so thoroughly reworked in 1966 because van Vogt was uneasy about the original material and reluctant to release it in 1944 under his own name. While that is certainly a possibility, such extensive revision could just as easily be symptomatic of van Vogt's almost infamous need to ceaselessly tinker with his stories.)

Aside from the sources already mentioned, there are further indications that van Vogt wrote the Hull stories entirely by himself. Stephen Clauser, who a few years ago was entrusted with the monumental task of sorting through and organizing van Vogt's tremendous amount of manuscript material, told me in a 2002 email message that he had come across revised drafts of the Hull stories where van Vogt is given sole credit in the byline. Clauser interpreted this as further confirmation that van Vogt did indeed write them by himself. (I'm embarassed to admit that at the time I was unwilling to accept this so I dismissed Clauser's information out of hand. I hadn't read the Campbell letters until around mid-2003, and couldn't bring myself to completely accept what they said about Hull until late 2006.) Apart from the obvious, this also shows that at some point van Vogt at least considered publishing revised versions of these tales under his own name.

For me the most uncomfortable aspect of this whole issue is easily the chapter about Edna (Chapter 12) found in his autobiography. He gives detailed anecdotes on the creation of some of these stories and praises Edna's skill as a writer. With the knowledge that he himself wrote these stories, one is left with an odd feeling of bewildered embarassment when reading this material. I believe it is worth repeating here what I said at the beginning of this essay: At worst I explain away his public statements on this matter as white lies necessary to maintain a writer's "professional secret." As to why he truly wished to keep this a secret is anybody's guess.

Another source of Hull anecdotes is worth noting. In his letter to Harlan Ellison that appears in the 1971 book Partners in Wonder (which contains their collaborative story "The Human Operators"), van Vogt says more about Edna and her SF stories, most notably some background on her first story "The Flight That Failed" (aka "Rebirth: Earth"). Since discussing collaboration, he may have felt obligated to talk about the Hull stories which he occasionally claimed to have collaborated on, and decided to stick with the "official version" of events in order to have the opportunity to say more on the subject. Or perhaps he did not feel comfortable with the idea of being forthright on this matter, since he apparently did not know Ellison well at that point. Or perhaps the original letter was different from what eventually appeared, that it was altered before publication at van Vogt's request when he learned that Ellison meant to include it in the book... Etc. etc. etc.

...We could endlessly spin theories here — and that's all they really are — but what it boils down to is this: we don't know. But we do know that our most important source for the background to the Hull stories, the Campbell letters, were apparently published before van Vogt ever got around to reviewing them for content. He very well may have held back permission, or insisted that they be edited, if he had known they would "let the cat out of the bag." Assuming he was being conscientious with the Ellison letter, one can also assume that he would have been just as cautious with the Campbell letters if he had ever gotten around to them.

Although Edna clearly did not write the Hull stories, the basic substance of these anecdotes nevertheless does sound plausible even if the roles are mixed up and the details embellished. I grant that it is common to gain inspiration from conversations with people, and especially with family members, so in that sense Hull undoubtedly played a role in the creation of all his stories. Retyping stories for him definitely would have enhanced this role, as is further attested from the background to his collaboration with James H. Schmitz, "Research Alpha." Perhaps the Hull stories were inspired this way — or perhaps she worked to some extent with him on these tales — but the evidence indicates that, if this is the case, hers was at most a minor role and that she was not even as much as a co-author in the conventional sense of the word.

The greatest unsolved mystery of this whole matter is the question of why he continued to give her credit for these stories when the reason for using the pen-name in the first place was no longer relevant. Even as early as the 1950s he could have easily admitted to writing these tales and it would have been perfectly acceptable. All of Heinlein's Anson MacDonald stories later appeared under his own name in book form and nothing odd or scandalous was thought of it. Perhaps even from 1950 onward van Vogt wanted to keep his options open for writing further stories under the Hull byline. Or perhaps he was being considerate for Edna's feelings by not "throwing away" the use of her name and continued it as a means of expressing his appreciation for her willingness to let him use it. And in the early 1970s Edna's terminal cancer may have reinforced his desire to keep things as they were, as a way to memorialize her name long after her death. However, at one point he must have at least considered publishing revised versions of these tales under his own name, as attested by the manuscripts found by Stephen Clauser (see above). Again, although one can endlessly theorize, we will probably never know the reason why he didn't go ahead and do this.

Examination of the copyright information on the Hull stories is rather interesting, and helps to emphasize that for whatever reason van Vogt went to great lengths to present Edna as their creator. (All of this information is gleaned from the acknowledgments pages in various books.) As a general rule both the original copyright, and the copyright's renewal done in the 1970s, were done under E. Mayne Hull's and not A.E. van Vogt's name. In many of the collections containing Hull's stories the holder of the original copyright is often the publisher of the magazine where it first appeared, such as Street & Smith (which later became Condé Nast) for Astounding. Many, if not all, of these stories were later copyrighted under Hull's name. Planets for Sale is particularly noteworthy — it was originally copyrighted in 1954 under E. Mayne Hull's name. The first edition was credited to Hull alone, and this fits in with van Vogt's initial effort to have the book published without his name associated with it. (This could fit in with a wish to have a "blind taste test" on the book, as theorized above.) The book's copyright was renewed in 1970 under both their names, undoubtedly as part of the publisher's attempt to aid the book's paperback sales by listing A.E. van Vogt as co-author on the cover.

...Of course, all that said, although it is extremely unlikely it is at least conceivable that Edna truly did write these stories and that the E. Mayne Hull "pen-name" was not a pen-name after all. Van Vogt could have submitted them to Campbell as his own, and any discussions about the Hull stories between the two in their correspondence could easily have been Hull's own ideas on the one hand and Campbell's suggestions in response on the other which was "relayed" through van Vogt. (Don's article develops this possibility more fully.) In this complicated world we live in, who knows? Sadly, van Vogt carried the full truth of this matter with him to the grave, so all we have to go by is conflicting accounts. But what little evidence we do have pretty conclusively illustrates that Edna was not their sole author, and almost certainly was not even their co-author. The information in the Campbell letters in particular must take precedence over his public statements on the matter — as an upfront private discussion between author and editor it is unambiguous, fits the facts, and explains most of the mystery surrounding these tales. On the other hand, inordinately complex theories are required to leave the door open — and even then only by the slimmest of margins — to the possibility that she did write them.

But, regardless of whoever wrote them, the Hull stories are truly remarkable works of fiction in their own right and have always fascinated van Vogt's readers. And that, really, is the most important thing, and not the tangled literary discussions which are of interest only to stuffy academics such as myself.