Readers of A.E. van Vogt have probably noticed that Van Vogt’s career as a science fiction writer is divided into two phases. His initial work in the field encompasses the years 1939 through approximately 1951. Then, from 1952 until 1963, he wrote very little new science fiction. He put together a number of "fix-up" novels, combining some of his earlier short stories into novels and, in 1957, expanded an earlier short story into the novel The Mind Cage. A large portion of this time he spent researching and writing a non-science fiction novel The Violent Man, published in 1962. Then, starting in 1963, van Vogt began writing science fiction again on a regular basis, beginning phase two of his career. He continued to produce "fix-up" novels consisting of his earlier phase one stories — plus, in some cases, new material, but phase two really goes into full swing with the publication of new novels starting in 1969. This review focuses only on those novels of entirely new material.

I have often thought about and tried to compare the two separate phases of his career, the early phase one works — which include many of van Vogt’s best short stories as well as the classic novels: Slan, The World of Null-A, The Players of Null-A, The Weapon Shops of Isher and The Weapon Makers — and the phase two stories and novels, which are largely forgotten and out of print.

Since many folks dismiss this second phase of van Vogt’s science fiction career, I thought it might be interesting to take a more in-depth look and see just how different those books are from his phase one works.

A quick review of the phase one works shows us that most of these stories and novels have hero protagonists with high moral standards and a basic desire to create a better world. Many of them are "supermen" — a recurring theme for van Vogt — but they are not supermen who look down upon the lesser humans (as was the typical science fiction superman up to that time), rather they see themselves as noble leaders or caretakers, whose role is to help humankind. Examples include the immortal Hedrock from The Weapon Makers; and the extra-brained Gilbert Gosseyn from Null-A.

Plots are fast paced — almost frantic — and ideas and far-out concepts are thrown at the reader with dizzying speed! The predicaments of the main characters drive and dominate the story’s plot.

I would describe the works of phase one as being "plot driven." The plot (often extraordinarily complex) is the primary focus. Plus, there is a great optimism that is present in phase one. Of the stories of this period, van Vogt was quoted as saying, "Science fiction, as I personally try to write it, glorifies man and his future."

So, how about phase two? How is it different?

As most fans of van Vogt know, he stopped writing science fiction in the early 1950’s when he became involved with Dianetics — L. Ron Hubbard’s system of psychotherapy. Van Vogt saw his involvement with Dianetics as a chance to study human behavior. His studies were mostly involved with a personality type that van Vogt called "The Violent Male" aka "Mr. Right." He also became fascinated with the behavior of women — especially in their relationships with various type of men. While researching his non-science fiction novel, The Violent Man, which takes place in a Chinese prison camp, he studied many aspects of communism and dictatorships including brainwashing and propaganda techniques.

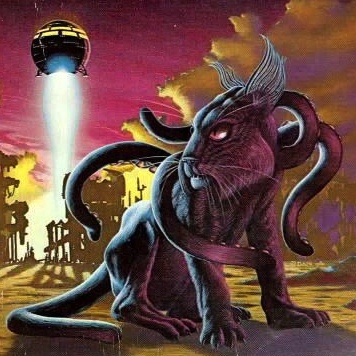

So, in 1963, when van Vogt begins phase two of his science fiction career, his interest in human behavior and sociological themes slowly begins to take center stage. I say slowly because his first novel of phase two, The Silkie (1969), is very much a phase one type story, with a far-out science fiction adventure with a moral hero-protagonist with "superman" type powers. His third phase two book, The Battle of Forever (1971) also has a moral superhero type in a far-out adventure story, but the amount of emphasis on human behavior themes is already increasing.

In-between these two books comes Van Vogt’s novel Children of Tomorrow (1970). This book is a very different van Vogt novel. Rather than "far-out," this book is written in a very straightforward manner, with none of the usual complications or unexplained plot shifts that van Vogt is known for. While the secondary storyline involves a clash between Earth and an alien species, the main plot has to do with an Earth family and their trials and tribulations living in Spaceport — the city where the families of the Space Fleet members live.

The main plot centers on a human behavior theme: How does a society — and the families within it — function when the men are out in space for 10 years fighting the aliens? Specifically, how are the teenagers brought up without their fathers being there? The resultant society, with its "outfits" (or official, organized, teenage gangs) is not only vital to the plot, but well thought out and presented. And for the first time in one of his science fiction novels, van Vogt’s main character is a "Mr. Right" character type. No science fiction superman here, but a human man with considerable flaws!

The other character types are all well done and each is unique. The honest, well-meaning daughter; the teenage male who tries to show individual bravado while trying to fit in with the group; the vengeful flirt who knows how to manipulate the boys; the twenty-something older womanizing man who preys on the teenage girls; the wife of "Mr. Right" who learns to cope with her husband and still find her own strength. All character types that we can recognize, but unlike some of van Vogt’s later phase two books, these characters seem very natural and we don’t feel that we are being "taught" about human behavior through them.

So far, after these first three phase two books, we have seen a different type of van Vogt novel, but there are still hints of phase one storytelling. We have seen an increase in human behavior topics, but have also seen Supermen–hero types and far-out science fiction.

The next six books, however, begin to show a clear difference between the phases, in my opinion, as behavioral and sociological themes begin to dominate. One would be hard pressed to say that any of these books "glorifies man and his future."

The Darkness on Diamondia (1972) is a rather confusing, unfocused book with too many themes, including male and female behavior, as well as themes on government.

In Future Glitter (aka Tyranopolis) (1973) a "Violent Male" dictator, and the society he creates, is depicted.

The behavior of women is explored in depth in Earth Factor X (aka The Secret Galactics) (1974). In that novel, various theories are presented regarding the relationships between the sexes.

The behavior of a spoiled, rich man dominates The Man with a Thousand Names (1974).

An anarchistic society, and how humans would behave in such a society, is demonstrated in The Anarchistic Colossus (1977).

In Renaissance (1979), van Vogt explores a society where the men have had their violent tendencies and their sex drives suppressed. Again, the behavior of men and women is a major theme.

So, at this point in van Vogt’s phase two science fiction, "human behavior" is now the primary focus.

This is not to say that van Vogt's phase one was devoid of anything but pure plot. The Null-A books are a prime example that the books of phase one could contain elements of human and sociological behavior as demonstrated by the general semantics philosophy that is part of the background of those novels. But, in phase two, the emphasis has shifted.

One book that exemplifies the difference between the phase one "plot" priority and the phase two "human behavior" priority is 1974’s Earth Factor X. This novel has an alien invasion as part of the plot — as does his classic phase one novel The World of Null-A. But in Earth Factor X, the alien invasion is almost just a backdrop for the real plot — man’s obsession with women and sex! The characters in the story — and therefore the reader, too — can’t seem to keep their minds on the invasion, and seem much more interested in their relationships with the opposite sex. It could be argued that the climax of the novel occurs when the character Metnov — after many hints and references about them throughout the book — finally discloses his theories on women!

Van Vogt’s phase two books also began to differ from his earlier works in the presentation of the main characters. Van Vogt has said that in his "newer" works, he began experimenting with using "neurotic" main characters. And in some cases he does, including the very convincing character study of the neurotic, spoiled, rich male in The Man with a Thousand Names. These protagonists are often a far cry from the moral, hero types that appear in his early novels and again show the influence of his greater emphasis on human behavior. If a study of human behavior shows that people are selfish, unethical, and have many other negative character traits, then it is only logical to assume that many of van Vogt’s phase two main characters have many of these same traits. And they do!

Again using Earth Factor X as an example, we can clearly see the difference between the types of main characters in the two phases. Carl Hazzard is a bodiless brain encased in some sort of wheeled enclosure. He is an admitted "sex maniac" who was constantly unfaithful to his wife. At the end of the novel he is in the enemy invasion ship, but his greatest concern is not in stopping the invasion, but in trying to create a scenario where is wife cannot be in a relationship with any other man.

Hard to imagine phase one hero Gilbert Gosseyn having that outlook when he is confronted with the alien invasion in The World of Null-A!

This is not to say that the phase two main characters aren’t capable of good — or that they don’t often do the right thing in the end. Even Hazzard, when he has a chance, manages to send the alien ship back home before it can complete its mission of conquest.

Van Vogt’s last few books are interesting and make me wonder if, perhaps, van Vogt was trying to return to the more moral, positive outlook of his phase one stories.

His next novel, Cosmic Encounter (1980) demonstrates van Vogt combining the more moral aspects of phase one with the human behavior subject matter of phase two. Of all the phase two novels, van Vogt might have done his best job of integrating his behavioral observations and use of character "types" into a swiftly moving, adventure tale with a grand science-fictional theme. We get plenty of insight into the behavior between men and women, and the attitudes of persons of different social classes in England in 1704 — and the subsequent changing of those attitudes in time — but it is well presented within the framework of the story. And, even though the main character, Fletcher, is a murderous pirate at the beginning of the tale, we can see some of the old van Vogt optimism is his character's development towards becoming a more moral being as the story progresses.

And in the ending to the novel, not only has Fletcher transformed into a more moral being, but the entire universe — as a result of telescoping back in time before beginning its forward flow once again — transforms from a "child" universe to an "adult" universe. And van Vogt, as narrator, conjectures, "all human beings would live on a more responsive planet in a maturing solar system. No more infantile destructiveness."

Van Vogt definitely seems to be a returning to a familiar phase one theme — trying to make the world (and the entire universe) a better, more moral place, and the individuals within that universe into more moral beings.

This is further exemplified in his 1983 novel Computerworld, where the "heroes" are a group of rebels that are trying to defeat an increasingly dictatorial computer-run society. Not only is the computer the "bad guy," but its presence has the effect of reducing the morality of the individual — literally diminishing the human soul. The rebels, who have the ability to "become" other people — representing the ability to empathize — are moral beings trying to save society and "restore" the human soul. No neurotic, sex-maniacs in this group! And the group’s leader, Glay Tate, has some abilities that are reminiscent of van Vogt’s earlier superman type.

His final novel, 1985’s Null-A Three, is a continuation of the phase one series with the same moral hero Gilbert Gosseyn.

In the final analysis, none of these phase two novels approaches the excitement and impact of van Vogt’s best phase one works. While van Vogt’s behavioral themes and theories are often interesting, the emphasis on those themes create a less powerful story. By adding various psychological and sociological insights, van Vogt often creates a distance or disconnect between the reader and the viewpoint characters. We no longer "are" Jommy Cross or Gilbert Gosseyn — totally engrossed in their activities and thoughts. Rather, those thoughts are often interrupted by contemplations on human behavior.

In the more successful phase two books, van Vogt’s human behavior themes and theories are well integrated into the plot and the character types that he depicts are well presented and believable. In the less successful phase two books, the human behavior set-up or character type being studied seems to be the whole reason for the book and other plot elements seem forced and implausible.

In the "more successful" group, I would put The Battle of Forever, Children of Tomorrow, Cosmic Encounter and Computerworld.

In the "not-so-successful" group, I would include The Man with a Thousand Names (Van Vogt’s absolute worst book, in my opinion), Future Glitter, Renaissance and The Darkness on Diamondia.

Based on the entirety of the phase two works, I would argue that the novels of phase two should not be totally dismissed. There are glimpses of the earlier van Vogt — and some of the phase two works are quite enjoyable and interesting. I believe that it is primarily due to those middle six novels that van Vogt’s second phase has been judged as being inferior and forgettable. Alas, there are some really poor novels in this group, and the plots are very thin. But, on the whole, phase two still demonstrates van Vogt’s ability to write thought-provoking, fast-paced, sometimes confusing, but usually entertaining science fiction.

Regardless of whether the novels and stories are from phase one or from phase two, van Vogt’s body of work offers a unique style and viewpoint that is unlike any other science fiction author. And, for that reason alone, well worth reading!