Introduction

A.E. van Vogt was one of the most popular and prolific writers during the 1940s, producing more than forty short stories and five serialized novels (Slan, The Weapon Makers, The Chronicler, The World of Null-A and The Players of Null-A) between July 1939 and November 1949. Most of these works appeared in the pages of Astounding Science Fiction magazine, and his popularity at the time rivalled that of Isaac Asimov and Robert A. Heinlein, both of whom were also prolific contributors to the Astounding of the 40s.

Slan (Simon and Schuster, 1951) — one of van Vogt's real novels, not a fix-up.

(cover art © by Edward R. Collins)

During the 50s and 60s, van Vogt produced relatively little new fiction, but (with the boom in paperback publishing) most of his magazine stories were reprinted in book form. This was a natural thing for authors to do, because it was an easy way of boosting their income while meeting the demand from fans for stories they may have missed the first time around. All of van Vogt's novels were reprinted (with The Chronicler being retitled Siege of the Unseen), while many of his short stories were collected together in book form (a precedent had been set by Asimov and Heinlein, whose respective collections I, Robot and The Man Who Sold the Moon both appeared in 1950).

What distinguished van Vogt's reprints from those of any other author (and arguably contributed to his precipitous decline in popularity with fans) was his practice of reworking near-perfect short stories into what he referred to as "fix-up novels." Why van Vogt chose to do this is unclear, although it may have been a perception that novels sell better than collections. Unfortunately, the result was often tantamount to vandalism of some of the most imaginative and seminal short stories of early science fiction.

Any work of fiction consists of three main elements: Theme, Character and Plot. Of these, Theme and Character are the two elements that are important to the reader (i.e. the ones that determine whether a story is good or bad). The third element, Plot, is simply a means to an end. Good plots can make very entertaining reading, and van Vogt's plots are as good as they come. But unfortunately he seemed to view his short stories simply in terms of "plot units" that could be inserted into fix-up novels in a completely different Theme/Character context from the original intention. This is what makes van Vogt's fix-up novels so infuriating to the reader who is familiar with the original context, and baffling to the reader who isn't.

The two worst offenders are The War Against the Rull (1959) and The Beast (1963), which take some of the finest SF stories of the 1940s and scrunch them into a whole which is distinctly LESS than the sum of the parts. Another notable but less offensive example is Quest for the Future (1970), where the combining is done more skilfully and the original stories were relatively lightweight to start with. Here is a chronological analysis of each of these in turn:

The War Against the Rull

Interior art from the May 1948 issue of Astounding Science Fiction, depicting a battle between Professor Jamieson and a Rull riding on an antigravity plate. This is a real Rull, not a human-like Yevd.

(art © by Paul Orban)

-

"Repetition" (Astounding, April 1940)

This was one of van Vogt's earliest stories, and the first to focus on a conflict between two human beings (as opposed to human-alien conflict). The action takes place on Europa (a moon of Jupiter), and the conflict is between Thomas (an interplanetary explorer and statesman) and Bartlett, a Europan colonist. The story has plenty of action, but the action-conflict is less interesting than the psychological conflict due to the differing background and outlook of the two men (Thomas takes the big-picture, long term view, Bartlett has the narrow, blinkered view of an isolated rustic).

-

"Cooperate — Or Else" (Astounding, April 1942)

This, like most of van Vogt's early stories, is about a human-versus-alien conflict ("Repetition" was a rare exception). The human is Professor Jamieson, the alien is a large six-legged creature called an ezwal. The action takes place on a wild and inhospitable planet, with the ezwal intent on killing Jamieson because the latter has discovered that ezwals are intelligent creatures (which knowledge the ezwals believe will lead to their extermination). In the background of the story is another, more fearsome alien — a large, mysterious wormlike creature called a Rull. This is the common enemy against which man and ezwal must "cooperate or else"!

-

"The Second Solution" (Astounding, October 1942)

This is a loose sequel to "Cooperate — Or Else." It makes no mention of Rulls, and while Professor Jamieson is mentioned he is offstage and not a major character in the story, which is about a "second solution" to the problem of co-existence with the ezwals.

-

"The Rull" (Astounding, May 1948)

This is the real sequel to "Cooperate — Or Else," and the only story to talk about an all-out interstellar war with the Rulls. It again features Professor Jamieson, and describes a one-on-one confrontation between him and a powerful Rull, both of whom become stranded on an unihabited planet. As in the earlier story, the Rull is described as being large and wormlike, with thought processes and behaviour patterns that are a complete mystery to humans (and likewise the Rulls are baffled by human behaviour).

-

"The Green Forest" (Astounding, June 1949)

This story is completely different from the previous ones. It is set in a bustling world of businessmen, lawyers and trade unions, and deals with a three-way conflict between a human protagonist, Marenson, a human adversary, Clugy, and a group of aliens called the Yevd. But the Yevd are nothing like Rulls — their actual form is rarely seen, because "by mastery of light and illusion" they can pose as perfect replicas of human beings, and even pass themselves off as specific people (at one point, a Yevd impersonates Marenson himself).

-

"The Sound" (Astounding, February 1950)

This is another story about the Yevd — the same aliens as in "The Green Forest," set in the same bustling world as that story. However, this one has a completely different cast of characters — the main protagonist is a nine-year old boy named Diddy (who, rather precociously, shoots and kills dozens of Yevd spies in the course of the story). As in "The Green Forest," these Yevd are near-perfect human impersonators, with a mastery of colloquial English ("Okay kid, you can scoot along"). A far cry from the mysterious creature portrayed in "The Rull" ("Live Rulls were hard to get hold of. About one a year was captured in the unconscious state, and these were regarded as priceless treasures").

-

The War Against the Rull (novel, 1959)

Why should anyone think it necessary or desirable to combine these six stories into a single novel? They all worked perfectly well at their original length, and they have little in common — different characters, different settings, different aliens, different themes. Yet van Vogt crammed them all into the structural mess that is The War Against the Rull. He makes Jamieson (no longer a Professor) the hero throughout. The finely delineated conflict between Thomas and Bartlett on Europa becomes a hazily rationalized conflict between Jamieson and some female colonist on a fictitious moon. Marenson becomes Jamieson. Diddy is still Diddy, but now he is Jamieson's son. Worst of all, the Yevd are now Rulls! So in some chapters the Rulls are enigmatic wormlike creatures with utterly inhuman thought processes and behaviours, while in others they are shapeshifters who can make themselves indistinguishable from humans!

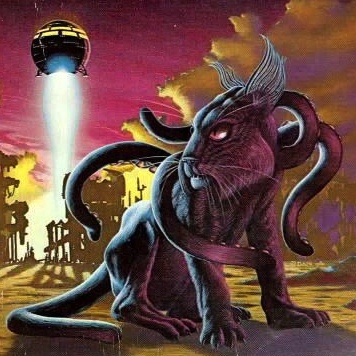

The Beast

-

"The Great Engine" (Astounding, July 1943)

This story has a fairly straightforward plot, and probably wasn't written with any sequel in mind. A man named Pendrake discovers a strange engine buried in a hillside. After a long and methodical examination he decides it must be part of an atomic-powered space drive. He traces the space drive to its owners, the Cyrus Lambton Land Settlement Project and, together with his wife Eleanor, finally solves the mystery — a group of scientists and philanthropists are working in secret to develop a utopian outpost on Venus.

-

"The Beast" (Astounding, November 1943)

This is a follow-on to "The Great Engine," but it shoots off in such a different (and totally wacky) direction that it's difficult to believe van Vogt planned it when he wrote the first story. This one is set in 1950, two years after the events of "The Great Engine." Pendrake discovers that the Lambton Project has been covertly infiltrated and taken over by a group of German Nazis (these are real, out-and-out Nazis who say "Heil Hitler" and take their order from the Fuhrer himself — remember that the story was written in 1943, when World War II was in full swing and Hitler was alive and well). The Germans are using the captured atomic rockets to fly to their bases on the Moon, where they exploit abducted females as slaves — Pendrake's wife Eleanor among them. By accident, Pendrake discovers there is another, much older human presence on the Moon — a huge cavern with an encapsulated Earthlike environment containing a group of people and animals who are seemingly immortal (unless they get killed by violence). The leader of these is a brutal, fascistic Neanderthal who van Vogt uses as a Hitler-metaphor. All the earthlings (except Pendrake) got there by wandering through a portal that has existed for millennia somewhere in the Western U.S. (in this story, it is a one-way portal whose origin is not explained). Eventually the story ends happily — Pendrake kills the Neanderthal (with a cry of "Hitler, how does it feel?") and the Americans defeat the Nazis and take over the flights to the Moon.

-

"The Changeling" (Astounding, April 1944)

Although it was first published in a single issue of Astounding, "The Changeling" is not really a short story but a novel in its own right (albeit a short one: 32,000 words). It is a well-constructed, logically plotted story, reminiscent in theme and structure of van Vogt's better known novels of the period, such as Slan or The World of Null-A. The hero is a man named Craig, who battles through a layer of false memories to discover that he, and his wife Anrella, are actually members of a group of unaging, telepathic super-humans. The action is played out against a political background in which a group of physically powerful feminists are seeking control of the United States. Needless to say, "The Changeling" contains enough ideas, enough characters and enough action for one novel — there is no need to merge it with other material into a fix-up monstrosity. Fortunately, The Changeling was published as a standalone novel by McFadden Books in 1967 (illustrated at right).

-

The Beast (novel, 1963)

The situation here is rather different from The War Against the Rull. In that case, we started with half a dozen short stories that worked perfectly well at their original length and had no reason to be novelized. In contrast, "The Beast" is a short story that is so bursting with ideas that it cries out for expansion. Up to a point, van Vogt did all the right things. He toned down the anti-Nazi polemics for a post-war audience, he explained (though still not very adequately) how the Earth-Moon teleport works, and he had Pendrake work out how to reverse it in order to get back to Earth (rather than having to be rescued by spaceship). Van Vogt also very sensibly used the earlier Pendrake story, "The Great Engine," as the first few chapters of the novel. All that needed to be done then was to add some new material to fill the gap between the end of "The Great Engine" and the start of "The Beast" — some action set on Lambton's Venus outpost would have done very nicely. But instead, van Vogt ruined everything by inserting the first half of "The Changeling" at this point (and then the second half of "The Changeling" at the end of the book). To do this, the hero of "The Changeling," who was named Craig, is now referred to as Pendrake. But they are completely different characters! Pendrake is, and has to be, a naïve but four-square everyman. Craig, on the other hand, is an existentially self-questioning superman. They are simply not the same person — a problem highlighted by the fact that "Pendrake" has (with no satisfactory explanation) two wives in this novel: a wife called Eleanor when he is the all-American everyman, and a wife called Anrella when he is the self-questioning existentialist! The book also has two completely unconnected political factions in the background — the (neo) Nazis of "The Beast" and the Amazonian feminists of "The Changeling"!

Quest for the Future

-

"The Search" (Astounding, January 1943)

This is one of van Vogt's nuttiest short stories, combining a non-linear narrative with a succession of surreal plot twists. The protagonist is a travelling salesman named Drake, who awakens in hospital unable to remember anything of the last two weeks. As he retraces his steps and meets various people, the events are gradually explained in flashbacks (although some of these events have not happened yet, because some of the people involved, including eventually Drake himself, are time travellers).

-

"Far Centaurus" (Astounding, January 1944)

This is a semi-comedy told in the first person by one of a group of astronauts travelling in hibernation (with brief periods of wakefulness) on a 500-year trip to Alpha Centauri. By the time they get there, they discover that faster-than-light travel has reduced the Earth-to-Alpha journey time to three hours, and that the whole Alpha system has been colonised by people from Earth! The story has a happy ending though — by judicious application of techno-babble they are able to go backwards in time and return to Earth just after they left.

-

"Film Library" (Astounding, July 1946)

This is another mildly comic story, about a film projector in 1946 (the story's present) which somehow gets tangled up with its equivalent in the (then distant) future of 2011. The 1946 projector starts showing footage of trips to the moon, bracelet radios, atomic guns etc, much to the consternation of the audience. The closest thing the story has to a protagonist is a college professor named Caxton, who brings the fun to an end by dismantling the projector and breaking its link to the future.

-

Quest for the Future (novel, 1970)

As fix-ups go, this one isn't really that bad. For one thing, the three original stories were all tongue-in-cheek to start with, and the fix-up reads as if van Vogt was trying to win a bet ("I bet you couldn't pick three stories at random and make a coherent novel out of them"). It starts with "Film Library," at the end of which Caxton loses his college job (as he did in the short story). He then gets a job as a travelling salesman (still trying to work out the secret of the projector), and we move seamlessly into "The Search" (with Caxton taking the place of Drake). Some of the original nuttiness of this story is toned down, and the world of the time travellers is rationalized to take in some of the elements from "Film Library," and provide better scope for novelization through the addition of new material (of which there is more here than in the earlier fix-ups). At one point in this new material, Caxton needs a means of travelling forwards in time, so he signs up for the 500-year trip of "Far Centaurus" (where he takes the place of the first-person narrator of that story). When the ship gets to Alpha, Caxton breaks out of "Far Centaurus" long enough to do what he has to in the future, then hops back into "Far Centaurus" for the technobabble return to the present day!

Other Fix-Ups

Having dealt with these three notorious examples, it should be said that most of van Vogt's novelizations are not really fix-ups in this sense at all — they simply follow the same practice adopted by other authors for converting short stories into novels. These can be divided into two categories:

Linking Together A Series of Related Short Stories

(Possibly with the addition of new material, but without the morphing of characters and twisting of ideas which typifies the true fix-up). Probably the most famous science fiction work of this type is Asimov's Foundation trilogy, which is composed of short stories originally published in Astounding during the 1940s. Van Vogt did this a few times with his own Astounding stories of the 40s:

-

The Mixed Men

(1952 novel based on the story series: "Concealment" — "The Storm" — "The Mixed Men," plus new linking material) -

Empire of the Atom

(1957 novel based on the story series: "A Son is Born" — "Child of the Gods" — "Hand of the Gods" — "Home of the Gods" — "The Barbarian") -

The Voyage of the Space Beagle

(1950 novel based on the story series from Astounding: "Black Destroyer" — "Discord in Scarlet" — "M33 in Andromeda," plus another closely related story from a different magazine)

(Two comments on The Voyage of the Space Beagle:

- The last of the three Astounding stories, "M33 in Andromeda," introduces a new character, Grosvenor, and a new science, Nexialism. In the novel, these are both present from the beginning of "Black Destroyer," but this is done without vandalizing the other characters and concepts!

- The commander of the Space Beagle, an interstellar spaceship, is named Hal Morton. In another of van Vogt's early stories, "The Vault of the Beast" (one of the few to avoid any form of incorporation into a novel) there is a crew-member on an interplanetary freighter called Lieutenant Morton. The story is not dissimilar in tone to the Space Beagle stories, so it is to van Vogt's credit that he resisted any temptation to work it in as a prequel to "Black Destroyer"!)

Expansion of A Short Story Into A Full-Length Novel

Examples of this practice are Eric Frank Russell's short stories "And Then There Were None" (Astounding, June 1951) and "Plus X" (Astounding, June 1956), which were later incorporated into his novels The Great Explosion and Next of Kin respectively. A few of van Vogt's early Astounding stories received a similar treatment, albeit with the incorporation of later, non-Astounding material:

-

The Weapon Shops of Isher

(1951 novel expanded from two related Astounding stories, "The Seesaw" and "The Weapon Shop," combined with a later, but still related, story that appeared in Thrilling Wonder Stories) -

Rogue Ship

(1965 novel expanded from the 1947 Astounding story "Centaurus II," combined with a much later, related story published in If magazine in 1963, together with an unrelated 1950 story from Startling Stories) -

Supermind

(1977 novel expanded from the 1942 Astounding story "Asylum," combined with a much later, related story published in If magazine in 1968, together with an unrelated 1965 story from If)

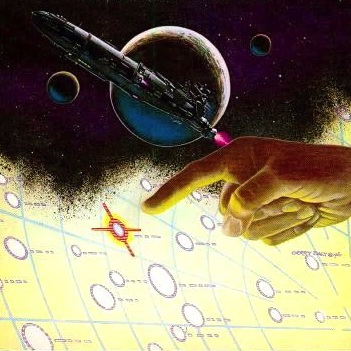

Cover of the December 1947 British reprint edition of Astounding (based on the original U.S. edition of June 1947), containing the story "Centaurus II" which van Vogt later expanded into the 1965 novel Rogue Ship. The Astounding story, which forms the first part of the novel, survives essentially intact — the major change being the alteration of the story's downbeat ending to permit a continuation of the action.

Cover of the December 1947 British reprint edition of Astounding (based on the original U.S. edition of June 1947), containing the story "Centaurus II" which van Vogt later expanded into the 1965 novel Rogue Ship. The Astounding story, which forms the first part of the novel, survives essentially intact — the major change being the alteration of the story's downbeat ending to permit a continuation of the action.

Another of the novel's ingredients, "The Twisted Men" (originally published in Super Science Stories in March 1950) fares less well, its characters being twisted still further to furnish the concluding part of the novel. The book's middle section appeared as a much later story ("The Expendables," in the September 1963 issue of If magazine), but this was probably written after van Vogt had planned the fix-up in his mind (it combines the spaceship name from "The Twisted Men" with character names from "Centaurus II").