The following interview is copyright ©2006, 2011 by Isaac Walwyn.

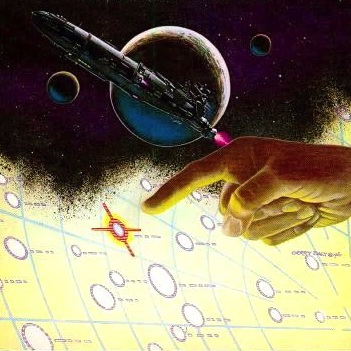

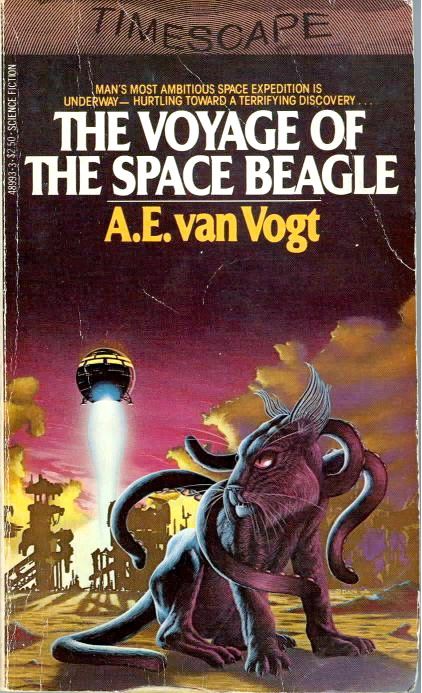

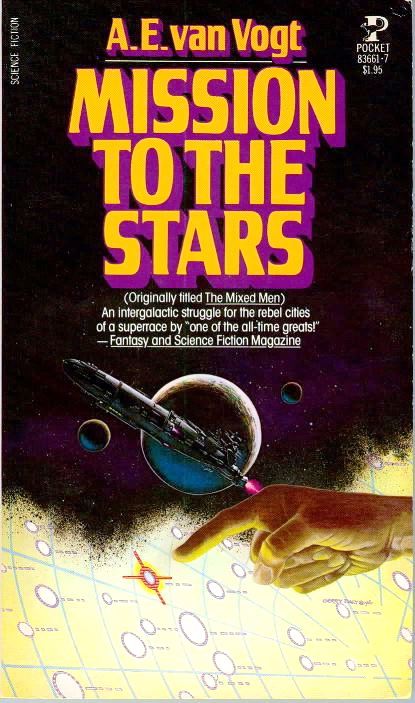

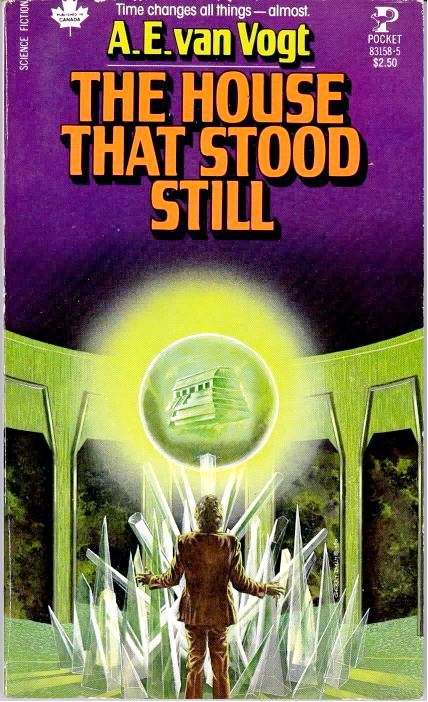

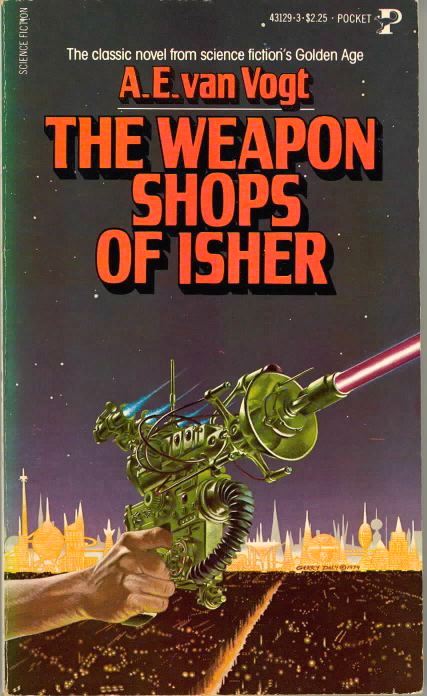

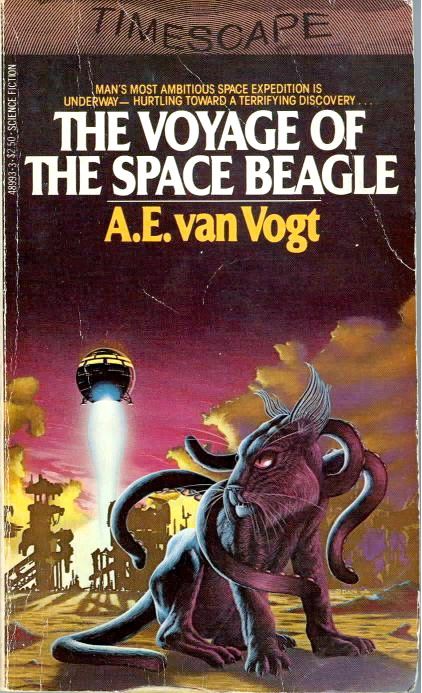

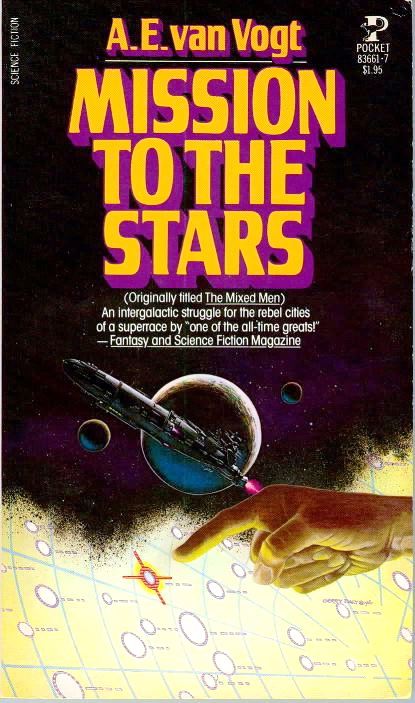

Like any SF fan, I have a mental list of my favorite book covers. Remarkably, unlike any other artist, all four of Gerry Daly's covers for van Vogt novels hold places of special honor on that list. Indeed, when creating the navigation banner at the top of every page here on Sevagram, I felt that Gerry's covers best encapsulated everything marvellous about van Vogt, so both of the images in the banner are Gerry's.

Granted, he isn't a prolific artist, but what he lacks in quantity he's more than made up for in quality. Even from such a small sampling, it can be seen quite clearly that Gerry is one of the most talented illustrators ever to work in the SF field...

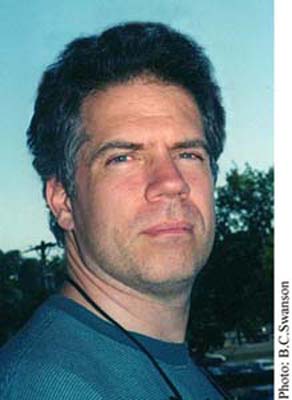

photo © B.C. Swanson

...And yet many of the world's greatest authorities on SF art are completely ignorant of Gerry and his work. His name does not appear in any of the SF art books or encyclopedias. The internet is completely bare of any information on him — just the occasional cover art credit. Imagine my surprise, then, when one day an email from none other than Gerry Daly appeared in my inbox. He had come across my site and decided to contact me. Not one to waste such priceless opportunities, I asked if he would be willing to be interviewed. He happily agreed, so I came up with a list of questions.

So it is with honor and delight that I am able to present this interview — which also gives a wonderful behind-the-scenes look into the world of book illustration — and hope that it will serve to bring more attention to this undeservedly neglected artistic genius.

(October 22nd, 2011 — Since this was the very first interview I ever conducted, I asked the occasional silly question which in retrospect I find deeply embarrassing. It's a great testament to Gerry that he nonetheless did his best to give a dignified answer to all my questions. In the years since interviewing him, I've regrettably lost contact with him, but I hope he's continuing to share his incredible talents with the world.)

| Isaac: |

First of all, I know how to pronounce "Gerry" but how do you pronounce "Daly"? Does it rhyme with "alley" or "bailey"? |

| Daly:

|

It rhymes with "bailey." |

| Isaac: |

How about some biographical data? When and where were you born? Do you have any brothers or sisters? Did you go to art school, and if so which one? You know, that sort of thing. |

| Daly:

|

I was born in Jamaica, Queens, an "outer borough" of New York City, on July 18, 1957. I am the eldest of five children; followed by a brother and three sisters, in that order. My family and I moved to Long Island — the "'burbs" east of the City — when I was three years old.

Drawing became my favorite thing to do by the time I started grade school. I honed my "eye" for images and colors in a mostly untutored way: sketching whatever caught my attention. I didn't take any elective art classes after grade school until my senior year in high school. By then I had decided that I wanted to be on the track to becoming an illustrator and thought that I should seek some guidance to that end.

By the end of high school I was awarded a full scholarship to the School of Art at The Cooper Union in New York City. I graduated from Cooper with a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree. Some of the credits toward my degree were from classes that I took at Parsons School of Design on an exchange-student basis from Cooper Union in my junior and senior years. It was at Parsons that I was able to take illustration classes — taught by actual, working illustrators. And it was at Parsons, actually, that my career as a freelance paperback cover illustrator was given its start.

|

| Isaac: |

How did you first get involved in doing cover art for books? |

| Daly:

|

One of the classes I took at Parsons during my senior year in college was called "Illustrating for Paperbacks." This class was taught by the head art director of Pocket Books at the time, Milt Charles. Along with offering his students an insider's perspective on what the publishing business expected from artists, and giving tips on what the pro's use for art techniques and reference material, Milt offered an actual book cover commission to the most promising student. I was chosen as that student from that class. That was quite a jump-start to my career! My expected career path in Illustration was to start out doing lowly black-and-white spot illustrations in order to get printed pieces for my portfolio, and build from there.

After that first cover assignment, I gratefully accepted a steady stream of commissions — one after another from Milt at Pocket Books — for about the next seven years.

|

| Isaac: |

As far as I know, you seem to have worked mainly for Pocket Books' line of science fiction novels. How much did you work elsewhere, and for whom? Do you have a special affection for the genre, or is that just the way things worked out? |

| Daly:

|

I'll answer that last question first: I've long been interested in science and technology, and was an avid follower of the American and Soviet space programs from my pre-teen years on. When I discovered science fiction novels as a teenager I felt as if whole worlds opened before my mind's eye. I was drawn to the scientific concepts, as well as the imagery, found in science fiction — and I thought most of the science fiction book cover art was cool, too. Much of the artwork that I was attracted to and wanted to learn from as an art student was science fiction- and fantasy-oriented. In addition to taking the requisite art lessons from the work of the Old Masters, I tried to learn from such contemporary examples as the rock album covers of Roger Dean and H. R. Giger, the aerospace art of Robert McCall, and, of course, the best of the cover art of science fiction paperbacks. My favorite covers were those done by John Berkey, Paul Lehr and John Schoenherr.

Steeped in all that visual and literary input, it was inevitable that I sought to do science fiction-related art when I was starting out in my training as an illustrator. The chance to someday create the kinds of images that amazed me as a reader — and then to see them published! — was a big motivator in my years of study as an artist.

It's true: I had worked mainly for Pocket Books, though my science fiction work for them was bookended by work in other genres. In my first year as a professional illustrator I did covers for about ten or so Pocket Young Adult paperback titles. Then, as I had done in the "Illustrating for Paperbacks" class, I asked for science fiction assignments. I did a run of about a dozen Science Fiction titles — in either paperback covers or hardcover jackets — for Pocket before they began asking me to do paperback covers for murder-mysteries series and crime/espionage novels.

Among my other illustration clients during and since my "Pocket Books era" were: The New York Times (Science Times section); Random House (Star Wars/The Empire Strikes Back punch-out-and-make-it, pop-up, and activity books); Penguin Books (Young Adult fiction paperbacks); The Book of the Month Club (art for promotional brochures); covers and interior illustrations for various industry and specialty magazines (for which I won two awards); and a smattering of art for a small New York ad agency. Also, for the past twenty years I've been commissioned to do paintings and murals for a number of private clients.

|

| Isaac: |

What other artists are you acquainted with? |

| Daly:

|

There are a number of artists and illustrators with whom I've been acquainted over the years, although I haven't been in touch with them all that much lately. I was closest to three illustrators in particular; extremely talented guys who are "household names" in their respective specialties: Wayne Barlowe, Joe De Vito, and Murray Tinkelman. Murray is also an excellent and well-liked educator in illustration. He was, actually, a mentor of mine, to whom I am eternally grateful: Murray played a big part in my career-building path during my time at Parson's School of Design. |

| Isaac: |

I've always wondered about the process of doing art for publication, so the next few questions will relate to that. If some of these questions strike you as the product of extreme idiocy, please bear in mind that I know virtually nothing about such things but I am eager to learn, and sometimes a stupid question is the only kind of question.

To start with, does a publisher approach you to do a specific cover just out of the blue? Or have you often had previous contact with whomever commissions the art?

|

| Daly:

|

An illustration commission can come about in any number of ways; though, very rarely "out of the blue." When an illustrator is already popular and well-known, it's not unusual for him/her to be sought out by art directors to lend his/her unique visual approach to a project. Yet, all illustrators are occupied, not only with creating, but with getting their art noticed in the sea of images that's out there in print and on the Internet. They promote their work by sending sample reproductions to likely clients, or by having their work showcased in a printed illustrators' directory or in an online gallery. Some illustrators have an artists' agent that handles the promotion of their work and pricing negotiations for them.

I've obtained my commissions in several ways. My Pocket Books work was through a previous association with the art director. Then there was a client that I gained through being recommended to them by a fellow illustrator. The rest of my clients were solicited through my own self-promotion.

By whatever path the illustrator comes to the attention of an art director, when his/her work has sufficiently interested an art director, the illustrator is invited to a meeting where the project is discussed. Also covered in this meeting are the scope of the intended use of the art, the fee offered the artist for that use and the production schedule of the book. If the illustrator agrees to the fee offered and all the terms — and the art director to any counter-terms — a contract is signed and the illustrator heads for his/her studio. An illustrator who is "repped" will have most or all of this negotiation handled by his/her agent.

|

| Isaac: |

On the average, how much time do you have to complete the painting? |

| Daly:

|

At the time I was doing science fiction paperback book covers for Pocket Books — the 1980s — the majority of the commissions involved lead time of up to 3 or 4 weeks from the moment of commission to the time the final artwork was needed. Naturally, this time frame also included reading the manuscript, generating sketches and working out the final cover art concept details with the art director. In my experience, at that time, paperback covers had one of the most generous lead times of all publications using illustration. These days, from what I hear, the schedules of many publications seem to have tightened up across the board. |

| Isaac: |

I think it's fair to say that the cover is one of the main selling points of any book. For instance, when I'm browsing in a bookstore my eye is often caught by an interesting title. But once I pull it off the shelf, it's the cover that creates the first powerful impression of the the book — one's imagination starts spinning immediately, and a whole new world is vaguely formed in my mind. This vague world is often enhanced or crushed by the blurb, but that initial impression is truly indelible. In view of this important role in the book-buying experience, I imagine the cover artist would be well rewarded for his efforts, but the real world is seldom as fair as that. So if you'll excuse the indelicate question, may I ask how much money an average cover commission earns? |

| Daly:

|

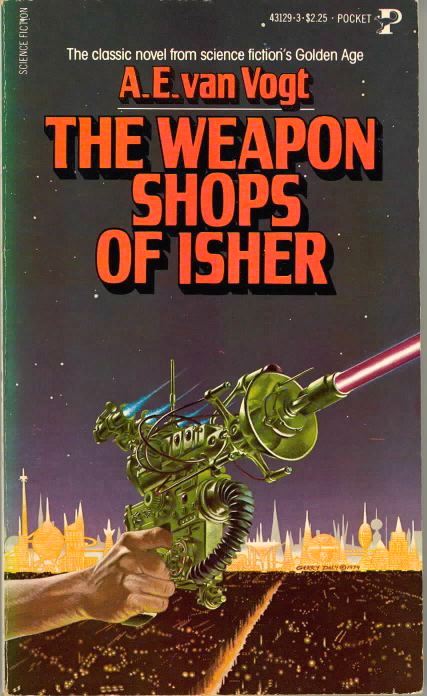

My "science fiction period" with Pocket Books began during the first year of my career as an illustrator, and so I didn't "command" as much as what a better-known artist would have gotten. The van Vogt covers were commissioned during my first two years, and to the best of my recollection averaged about $1,700 per cover — for reproduction rights only. I got two, and sometimes, three commissions a month; so this was good money for someone just starting out. |

| Isaac: |

How big is the painting? |

| Daly:

|

I've painted in a variety of sizes for paperback covers. I started out doing 20"-x-30" paintings for "full-bleed" covers. "Full-bleed" is where the image goes right to the edge of the cover. This size painting also included the "bleed," the extended border space around a painting. "Bleed" offers the art director the option to re-center the art on the cover, or to change the size of the art relative to the cover, if necessary. My science fiction cover art, unlike the other genres I've painted for, varied little from the 20"-x-30" size because of the level of detail I wanted to depict in an image for a "full-bleed" cover. |

| Isaac: |

Is the image transferred to the book cover using photography, or some other method? |

| Daly:

|

Art for print reproduction is traditionally photographed, but with the development of new technologies, other processes can be involved. In the mid-1980s, laser-scanning of art done on flexible supports, such as paper, became an option. Now, more and more, digitally-created artworks — which are very popular in today's science fiction covers — are files fed directly into computerized printing presses. Any of these methods are used to create the traditional set of four-color plates that are still used to print covers. |

| Isaac: |

What generally happens to the painting once it's been photographed for the cover? Do you keep it? Does the publisher own it?

And what about the image's copyright status? People (myself included) nonchalantly fling about scans of book covers, though the images are presumably owned by somebody. Do you own the rights to the painting, or does the publisher? Do the rights revert to you after a predetermined period of time?

|

| Daly:

|

The issue of copyrights is not a small one for the artist. The creation of a piece of art inherently generates a bundle of rights — along with, of course, a physical painting — that are owned by the artist. Embarking on an art commission entails hammering out a contractual agreement with the client. In the case of book covers, the client is a book publisher, who is represented by an art director. The particular use of the art that the client intends determines the extent of the rights purchased by the client. For example, the artist is paid a bigger fee if the book he's illustrating for is going to be marketed to a larger geographical area than just North America. Many possible factors such as the celebrity of the author and whether the book is involved with other media, like movies, could also contribute to the extent of the rights sold. Simply put, the fee is commensurate with the extent of use of the art.

The common arrangement for the average American paperback cover — or hard cover dustjacket — is for the purchase of one-time North American reproduction rights for the book cover and for promotion of the book, with the artist retaining ownwership of the physical painting and all other rights that are not purchased. The art buyer prepares the contract so that it includes the agreed-upon price and other particulars such as deadlines. Once the contract is approved and signed by the artist, s/he can go ahead with the work.

As an actual example regarding commensurate fees: Some weeks after completing a particular science fiction paperback cover commission, I was contacted by the publisher and told that a Japanese book publisher wanted to use my art for their edition of the book. I gave permission for the art to be used and was paid another fee for the rights to use my artwork on the Japanese cover.

On the issue of artwork being tossed around the Internet: I'm OK with my art appearing on a non-commercial website — as long as I'm given copyright "©" credit adjacent to my artwork. I've been pleasantly surprised that my covers have appeared on the Web as they have — on Icshi.net and other Van sites. However, if someone were to copy a JPEG of book cover art from any site and use it without the copyright holder's permission: that's a copyright infringement. The Internet has opened up a real "can of worms" regarding the use of protected works. Th

|

| Isaac: |

Is it possible to register an artistic work with the U.S. Copyright Department, in the same way that it's possible to send in a manuscript? If so, exactly how does one go about it? I'm assuming you don't send them the actual painting... |

| Daly:

|

No, this is a relatively simple procedure, I'm told — since I have not registered any of my works yet I cannot give too many details about it. Generally, artworks are registered with the Copyright Office using an application form and instructions that you can download from their website. Some of the requirements in registration are that one supply details about their work(s), note any derivative sources for the work and include a representation of the work in the form of slide(s), photo(s) or the like, with the application. Registering a creative work reinforces its inherent copyright protection and helps a great deal in any disputes about infringement that may arise down the road. |

| Isaac: |

Now that we've dealt with the generalities, let's get down to specifics. I've always been struck particularly by the almost "iconic" style of your covers — the focus on a single emblematic image, a simple yet effective thematic encapsulation of the entire book. How are you able to achieve so much with so little? I get the impression that when you read a book in order to create a suitable cover for it, you're especially sensitive to the "feel" of the story as well as the setting, and that you try to capture this in your paintings. |

| Daly:

|

Thanks for the compliment! My aim is to go for an attention-getting solution to my illustration assignments. After all, as Milt Charles pointed out in his book cover class at Parsons, a book's cover design needs to be its own advertising poster on the bookstore shelf.

I read the entire book or manuscript whenever possible in order to discover its essence — to see what the central theme is, to and learn if there is a central character or powerful scene to portray without giving away the plot of the story. Sometimes the author's turn-of-phrase will strike me a certain way and cause something about the story to loom large in my mind's eye. Then I "go for the jugular" with an image that will catch the eye as well as stimulate some curiosity about the book. A big source of satisfaction for me is to hear that a reader has bought a book based on my cover art and then has identified the book with that cover once he/she has read it.

|

| Isaac: |

When you were working on the four van Vogt covers, did you toy with different scenes to depict from each book before deciding on one in particular? And did you have several different approaches to a single scene before deciding on one interpretation? |

| Daly:

|

In doing the sketches that I would show to the art director for final approval on the cover image, I tried to get as many different ideas going as I could. Sometimes a book would inspire "narrative" images: certain exciting or dramatic scenes from the story that might typify the book or just look interesting. On the other hand, the book may suggest what I call "conceptual" or "symbolic" images. This would usually be when the story has a theme that's stronger and more representative than any action occurring within it. Obviously this "conceptual" image would be some person, critter or object from the story, or something that could have conceivably been in the story. Sometimes a book will offer both "narrative" and "conceptual" ideas. I'd sketch whatever it would suggest to me.

I'd bring the sketches of the strongest ideas to the meeting with the art director, and he'd pick what he thought would work best. He sometimes had some input as to some detail that he wanted to make sure was included in the image — if he didn't see it in the sketch.

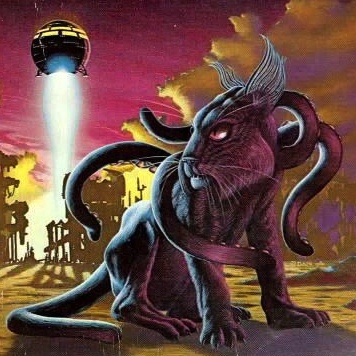

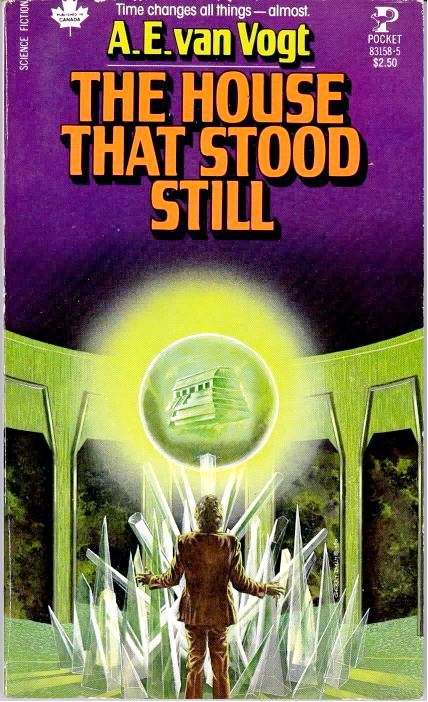

My cover art for The House That Stood Still and Voyage of the Space Beagle were narrative images, yet I did also come up with some conceptual cover ideas for each of them in the presentation sketch stage. The solution for Weapon Shops of Isher was always a "conceptual" idea in my mind and ended up as such a cover. Mission to the Stars inspired both types of images, yet my "conceptual" version was the strongest image among my sketches.

It's very interesting to see the varied — or sometimes consistent — artistic approaches to the van Vogt books over the years. That's the cool part, for me, about your Icshi.net site: the opportunity to compare covers and see how the books struck other artists over the years.

|

| Isaac: |

Which of those four painting did you most enjoy creating? And which are you the most satisfied with now, twenty-five years later? |

| Daly:

|

I had fun doing all of those paintings. Each one involved my doing some model-making to assist me as reference in the rendering of certain items in the paintings. I made and photographed a kit-bashed raygun and space-battleship, and a plasticine Coeurl. A pile of glass shards served as a model for the crystalline objects seen in the House cover.

The painting that I am the most satisfied with now is the one that I think holds up the best after all these years: the art for Mission. Of course, I feel that I've improved a bit in my painting since then and would welcome a crack at redoing any of these covers for a new printing of the books.

|

| Isaac: |

Do you still own any of these particular paintings? Do you sell any of your paintings to individuals? In short, can I buy one? |

| Daly:

|

I still own the original art for all four of the van Vogt covers that I did. Of all my other published work, there were only three pieces that I sold. The buyers were people who were actually involved in some way that led to my doing a cover: an author, a model and a print producer. The paintings that were sold went for eight-hundred to twelve-hundred times the cover price of the publications for which they were created. |

| Isaac: |

Oh well. It was worth asking!

What sort of things are you up to nowadays? Book covers, or something else? How much non-commercial art do you do? In other words, how much do you do for your own satisfaction? And what subjects do these personal works cover (SF, landscapes, nature scenes, etc.)? For instance, apart from his SF work, John Schoenherr apparently does a lot of nature scenes.

|

| Daly:

|

I've recently moved back to New York City from midcoast Maine; and I'm currently reworking my illustration portfolio for a re-entry into the illustration market. My last commercial illustration assignment was an editorial piece, in late 2003, for a financial newspaper/magazine publisher.

At this time, the majority of my paid work — as it has been for the past twenty years — consists of painting commissions from private clients. These commissions have been mostly medium to large panel paintings. They've been a chance for me to explore other styles and techniques in my painting as they have ranged from decorative and graphic to impressionistic.

For one of my regular clients, in addition to paintings, I've done decorative wall finishes, and I've painted a mural in each of her two New York homes. This coming Fall, I'll be doing another mural for this client in her winter residence in Nevada. The themes of these murals are a departure from my previous work for publication. One of the New York murals is completely abstract and decorative. The other murals are pictorial and whimsical, in a certain way. They depict fantasies of anthropomorphized animals. In one, people-sized ants in 1940's garb are seen spending a Sunday in the New York City's Central Park. In the other, a menagerie of animals dressed as cowboys whoop it up in an Old West saloon. I appreciate the chance to do these private commissions for both the challenges and the variety that they offer, and I consider myself lucky to have such supportive and fun-loving private clients.

In terms of personal work, I make time for it whenever I can. It helps me to "exorcise my demons" and exercise my vision. My artistic vision tends to work in either hyper-conceptual, science fiction or fantastic terms, so I am usually working on something in that vein when painting for myself. On the other hand, I've also been inspired to explore plain ol' terrestrial landscapes, recently, after having spent four years as witness to the natural beauty of Maine.

|

| Isaac: |

Well, Gerry, I've really enjoyed this opportunity to converse freely with my favorite SF artist. If someone had told me a year ago that I'd be interviewing Gerry Daly, I would have called them nuts. Opportunities like this happen very rarely in one's lifetime, so I really appreciate your willingness to be cross-examined like this, to share more about yourself, and to give such a wonderful insight into your artistic creations. |

| Daly:

|

You're very welcome. It was a pleasure. Thank you for your interest in my work, for the kind words, and for highlighting, in your website, the role of the cover artist in SF publishing. I wish you good luck with the website, and with all your endeavors. —And I look forward to seeing what Icshi.net has to offer in the future. |