complimentary copy provided by the director.

January 17th, 2005

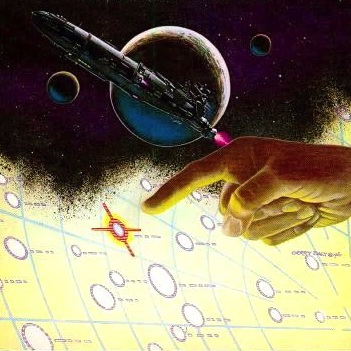

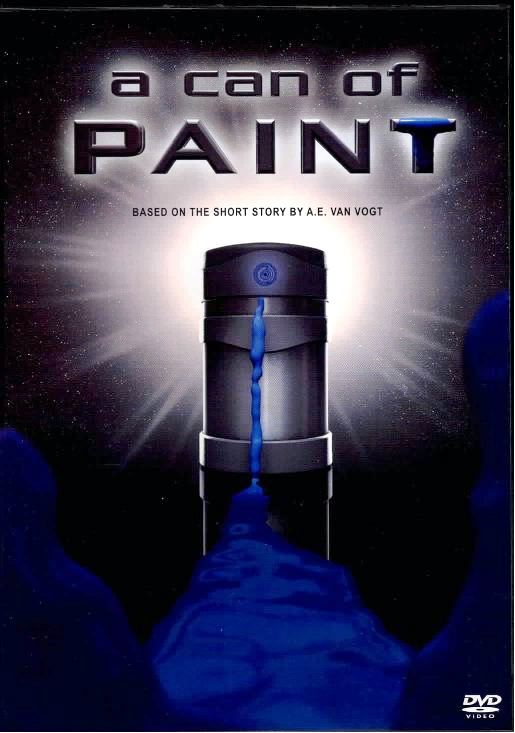

"A Can of Paint," first published in Astounding Science Fiction over 60 years ago, is still one of A.E. van Vogt's most famous stories. It pits one man's intelligence against a surreal and apparently insoluble problem: how to get a bizarre kind of alien-manufactured paint off his body before it finishes spreading over his body and kills him. It is therefore not surprising that filmmakers Robi Michael and Winston Engle chose this unique tale as the basis of their new short film.

Winston Engle, who wrote the screenplay in addition to being the executive producer, did a fine job adapting van Vogt's story. Several changes were made to the story's details, but when translating a work of literature into a visual medium certain changes must be made. The alterations were wise ones — far from detracting from the original source, they enrich it and maximize its impact. The story's setting is constrained to the interior and exterior of Kilgour's spaceship, and in turn the ship is floating in the void of space docked with an alien wreck. By doing this the film's creators not only save themselves having to build a whole other set, they also place all the emphasis on Kilgour and his plight. The addition of the computer (giving someone for Kilgour to talk to and discuss possible solutions), was a stroke of genius, as it would have been extremely difficult to film the story as it is with only one character and his internal monologue. Engle also injected a lot of humor into the story that was a welcome addition, and it blends in naturally with the script as a whole. Kilgour's solution to the problem was difficult to understand, but then again van Vogt's original story also had a similarly cryptic ending, and by and large the film version makes a little more sense.

The two actors involved, Aaron Robson (who portrays Kilgour) and Jean Franzblau (who did the voice for the computer) did an excellent job, especially since both were effectively acting by themselves — Robson on the set, and Franzblau doing the voice-over in the studio in post production. The interaction between the two characters is delightful to watch, with the computer offering serious, coldly logical suggestions and Kilgour countering with the natural, often humorous, retorts to some of its more extreme ideas.

There are only two difficulties in watching this film, one relating to the sound quality and one to Robson's accent (though this aspect should not be taken as criticism of Robson himself — it mostly adds difficulty in comprehension when combined with the poor sound quality). Firstly, all of his dialogue is faint and often hard to hear underneath the music and the computer's dialogue. But my brother — who has a degree in cinematography, and has been involved in making several short films — explained that when you record sound on the set, rather than adding it in post production, it's often difficult to get the quality right. Also, the quality of what was recorded on the set can be negatively affected during post-production when voice-overs, music, and sound effects are added. Secondly, Robson has a thick accent of a type which very few of us are accustomed to hearing — it almost resembles a Jamaican accent, though I've been told it is in fact British. This rendered his already faint dialogue doubly difficult to untangle, and was a topic of discussion every time I showed the film to someone. (With the additional consideration of his hairstyle, I almost expected Kilgour at some point in the film to commence shaking his head from side to side, swinging his dreadlocks around, singing Reggae tunes.) But many people will have trouble understanding him, and that includes people such as myself who were raised on a steady diet of British television programs like Doctor Who and Monty Python, and seldom have any trouble understanding any British accent, no matter how obscure. But all in all, I rather enjoyed seeing a man in space speaking with an unfamiliar accent, and it made for a nice change from the type of person we usually see in these kinds of roles.

The most impressive aspect of this film is the high production values of the visuals, especially James Lacey's exquisite make-up effects (and the time-consuming digital overlay done in post production to make the effect more convincing) simulating the liquid-light paint that Kilgour accidentally unleashes from its container and which begins to spread over his body. It doesn't resemble regular paint, but more of an ultra-smooth ethereal substance that is difficult to describe. They could not have done a finer and more imaginative job of depicting it. The set was well thought out and constructed, and Kilgour's ship really does look like a place that has been lived in constantly for an indeterminate amount of time. The faulty lamp on the workshop table was a nice touch, with Kilgour walking by it every now and then, absent-mindedly flicking it with his finger to get it to shine steadily. Overall, I found it difficult to believe this movie didn't have the budget of a feature Hollywood production. The quality of work put into this film by everyone involved — from Robi Michael the director, on down to whoever put the set together — reflects a level of care and professionalism seldom seen today, and this goes to prove that you don't need oodles of cash to create an excellent film.

Even what one might consider the minor details of this disc reflect this high standard. It comes in a professional-looking case like any movie you'd buy, has a fun menu screen, and includes some interesting extras such as a short deleted scene, production sketches, and behind-the-scenes photos so you can see some of the people involved in making the film. I'm pretty sure the disc is in universal format, so it can be viewed on a DVD player in any country regardless of which region, which I'm sure will be appreciated by you van Vogt fans in Europe, Asia, and elsewhere.

During the Christmas holiday I took the DVD of the film to my grandmother's house and watched it for the third time, this time on a big screen TV and with my whole family. It is indicative of this film's power that even my brother and grandmother, who do not care for science fiction in general, were fascinated by what they saw and enjoyed it very much. And even my dad, who likes science fiction — but not television or movies — seemed to really enjoy it. In fact my brother said he was greatly impressed by its technical qualities, with excellent lighting, make-up, set design, and directing, and added that it's one of the best short films he's ever seen.

Throughout the rest of my stay at my grandmother's, references to paint were rampant, with hardly a few hours going by without at least one of us making some kind of joke relating to paint — we were shopping in town, and went by a paint store. Someone immediately quipped that we shouldn't go in there even briefly since it could be extremely dangerous. Some of the walls in my grandmother's house needed repainting. And guess what we immediately started talking about. Some months ago, before I saw the film, I had bought my whole family some putty and set them aside as Christmas presents. On Christmas morning at my grandma's house we opened our presents. No sooner was one of the tins of brightly-colored putty opened than one of us started stretching it over his skin to make it look like the substance that coated Kilgour's arm.

It would come as no surprise for an outspoken van Vogt fan such as myself to lavish praise on a film adaptation of one of his stories, but the fact that it sparked the imagination of my usually sedate brother and grandmother like that is perhaps the best example I can give of just how powerful Robi Michael's film is. It's very impressive indeed, and a tremendous achievement in numerous ways. Incidentally, Michael informed me that Lydia (van Vogt's widow) saw the film at the screening in L.A. and was likewise impressed and pleased with it. I heartily recommend it not only to all you van Vogt readers out there, but even to your friends or relatives who tend to steer clear of sci-fi. In this respect, the film can serve as a perfect introduction to A.E. van Vog's vast world of fiction.