this novel can be read here.

read Denis Dubé's review.

September 26th, 2010

Not Without Its Charms

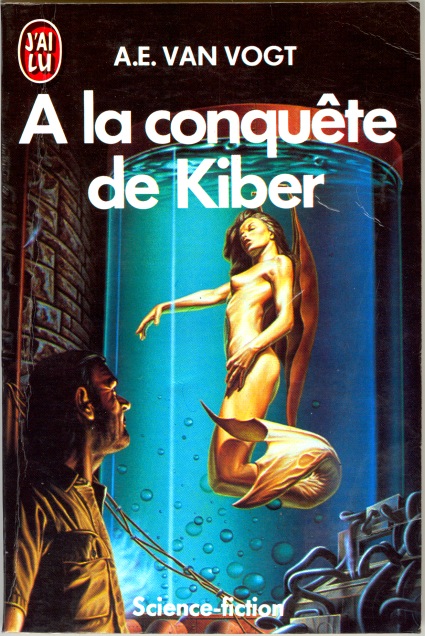

As I sit down to write this, I hear myself echoing many of Denis' sentiments. "Incomplete" is the key word that keeps cropping up when discussing To Conquer Kiber. It very much feels like van Vogt never gave it his full attention, and a strong indication of this is that it took him ten years of sporadic work before it was finally ready for publication. (And, to top it all off, it never appeared in English, only in a single French edition that was only reprinted twice and a single Romanian edition. No other editions, no other languages, nothing, meaning few publishers anywhere were interested in it even when it finally did make its appearance.) Usually, when van Vogt began work on something and then stopped, he never returned to it. Kiber was the exception. And since it is such an unexceptional novel, one is left wondering why he came back to finish this particular work. The answer will undoubtedly forever remain a mystery.

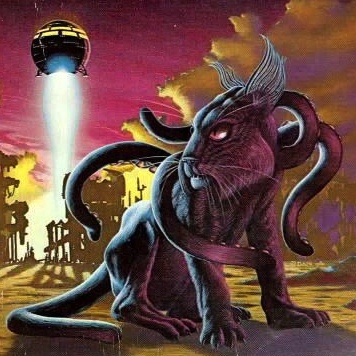

cover art © Barclay Shawn

(Incidentally, I remember reading — although I can't remember where at the moment — that in the '60s he was working on an idea for a novel to be entitled The Sea Man. Since Kiber was planned to appear in the mid-70s, I can't help but wonder if the two are in fact the same project. Craig's transformation into an amphibious creature — a "sea man" — certainly seems to suggest that the two are somehow related, and I can't imagine him creating two similarly-themed works around the same time. So Kiber very well could be the final materialization of the original Sea Man idea. If this is the case, then the novel's incubation period was even longer than ten years, and the story was already old, incomplete, and abandoned when he offered it to Wollheim in '75...)

Kiber certainly qualifies as his most disjointed and nonsensical story. It has its good themes (Craig's struggle with alcoholism) and some welcome moments of delightfully surreal humor (precognitive android Scotsmen!), but it all just totally fails to mesh together. It has many of the trademarks of van Vogt's fiction — the abductions, the sudden scene changes, the complex web of political intrigue — but it all lacks conviction. It is almost as if van Vogt was just going through the motions, or had lost his unique ability to make these tricky techniques truly work.

The cluttered style of Kiber — such as the incessant jumping around, the non-sequitur dialog, the aimless meandering — is highly reminiscent of the worst parts of Null-A Three (1984/5). Although this is a topic I often bring up when discussing his last few published works, I do think it is worth reiterating: I believe that Kiber's uncharacteristically chaotic feel further illustrates van Vogt's mental decline due to the encroachment of Alzheimer's, which began to show up in his books — with rather glaring suddenness — around 1984. But aside from all that, the mere fact that the novel remained incomplete for so long to me hints that he was never very satisfied with the direction it was heading, and that he was having tremendous difficulty getting it onto paper. (Always a bad sign for an author.) Although I've always felt that his later works are unjustly maligned, Kiber, sadly, has all the characteristics of belonging to his long, painful twilight years.

It's very difficult to know just what to make of the novel. Although it's a very strange and muddled book, being completely unintelligible in places, it is not without its charms. Surprisingly, I found myself really loving the idea of a precognitive android with an identity crisis who takes on the nationality of a Scotsman, simply because that was their last port of call and he took a fancy to their culture. We see a lot more of van Vogt's sense of humor in his later works (as I've said many times elsewhere), which I always enjoy tremendously. The book's atmosphere also has much to commend it, particularly the sea theme and the treatment of alcoholism, with the two making a strangely effective combination. And the political intrigue here is almost played for laughs, as we, the readers, are in as much of a daze about what's going on as the perpetually-intoxicated hero. When viewed this way, the book's plot almost becomes immaterial — it's Craig's reactions that are important, not what happens per se. This is strikingly different from most of van Vogt's work, and makes for a far more personal story than anything else he wrote.

Which brings us to another important point in the book's favor: Craig's struggle against alcoholism. Van Vogt usually didn't feature personal struggles such as this in his books — or when he did, he did it so badly that the reader cringes with embarrassment. I'm generally not a fan of character study in SF — much less from van Vogt who all too often allowed his bizarre psychological theories and Dianetics influence to override everything else — but his treatment of the character of Paul Craig is perhaps his best effort in this direction. This isn't the first seriously flawed character we've seen in a van Vogt story, but he is the most likable and sympathetically portrayed. We see him not as a villain, buffoon, or selfish egoist, but as a man suffering under the effects of a terrible addiction, and a man who would be capable of greater things if only he could finally break free of it. I very much enjoyed watching Craig's soul-searching journey out of alcoholism during the course of the book. This is especially true after the unexpected turn of events in chapter 21 when Craig finds himself back on Earth and tries to return to his old life after "being away" for so long, and he finds himself wondering of his offworld experiences... "Did any of that really happen?"

So, all in all, To Conquer Kiber is a novel that, despite its serious defects, is still worth a read, if only for its completely unique and peculiar qualities, and for the fascinating niche it fills in the overall understanding of van Vogt's work.

A Note of Thanks

One final note: were it not for Denis Dubé's exemplary efforts on making information about this rare and inaccessible work more widely available, in all likelihood I would never have been able to read the novel for myself, and none of you would be able to enjoy the wealth of information Denis has given us. What began as a personal project of his own, for his own enjoyment and edification — namely, translating the French version into English, and then writing a detailed summary — gradually developed into something that will benefit many, many others. I'd like to publicly extend to him my heartfelt thanks, as well as the thanks of van Vogt fans everywhere, for his invaluable contribution to the growing body of vanvogtian scholarship.