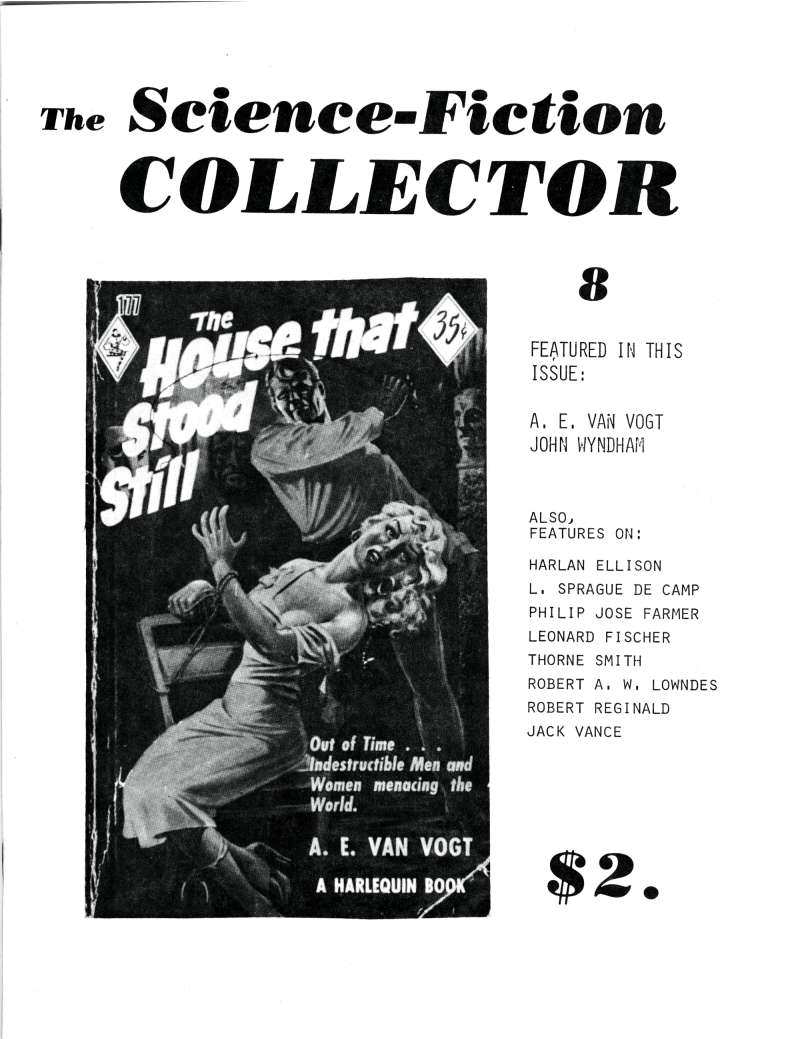

The following interview is Copyright ©1979 by J. Grant Thiessen. Originally published in The Science-Fiction Collector #8, it is reproduced here by kind permission of Grant Thiessen. Back issues of The Science-Fiction Collector are still available from the publisher, Pandora's Books Ltd.

A. E. van Vogt scarcely needs an introduction to most readers of science fiction. While he does not enjoy the status that contemporaries of his such as Isaac Asimov and Robert Heinlein enjoy, he shares one very important feature with these authors. Very little of his work is allowed to go out of print. It is only through a constant source of income that most authors can afford to remain full-time craftsmen, and surely the most effective means of achieving this is to continue to derive royalties from one's writing long after one has produced a piece initially. Hence, van Vogt's tactics have always been to derive the most steady income from his work. In fact, he has had some of his work published by very small publishers, or unimportant publishers, for one reason only — to maintain public awareness of him as a writer.

He has succeeded. Few writers have been published in as many languages as van Vogt, and he remains a most popular author, both on the bookshelf, and in the science fiction convention circuit as guest of honor. It was during a convention in Vancouver, B.C., Canada, in 1978, that the following interview was taped.

I have a personal reason for an intense interest in A. E. van Vogt. A collection of short stories of his (Away and Beyond) was either the first or second pieces of science fiction I read (the other was Arthur C. Clarke's Against the Fall of Night). So, he helped lay the cornerstone of my present career. In later years, I discovered that he had spent part of his life in the town of Morden, Manitoba (about 30 miles from where I sit now), and more years in Winnipeg, Manitoba (the nearest city to Altona, about 60 miles away). I have reproduced a picture of van Vogt's home in Morden on a subsequent page. For more information on van Vogt, I refer you all to the book, Reflections of A.E. van Vogt, his autobiography published in 1975 by Fictioneer Books. (see Bibliofile in this issue.) It is an excellent and entertaining autobiography originally done for the UCLA Oral History department, as part of a program of biographies of Americans who would nor ordinarily be the subject of a biography.

| Thiessen: |

Can you tell me what made you start writing in the first place? |

| Van Vogt:

|

Well, it was Depression time, and there was nothing else to do. |

| Thiessen: |

So, just lack of anything better. |

| Van Vogt:

|

[laughs] In a sense, there's a great truth to that, but, also I was a great reader. My mother takes full credit for my being a writer. Apparently, when she was carrying me, she said, she read an endless number of detective stories. |

| Thiessen: |

So why don't you write detective stories? |

| Van Vogt:

|

[laughs] Well, she wouldn't know the difference. |

| Thiessen: |

What authors do you feel influenced you the most in regards to science fiction writing. |

| Van Vogt:

|

Well, of course, I read the early Amazing but I also ran into a writer called A. Merritt who wrote in an unusually lush style with unusual ideas. The ideas intrigued me. The lush style I found a little fulsome, but still, it had its quality.

Writers that influence me in terms of excitement were not only in science fiction, but writers like Max Brand, who wrote westerns, and Edgar Rice Burroughs who wrote who-knows-what (or maybe we all know what).

|

| Thiessen: |

Yes. [laughing] |

| Van Vogt:

|

Tarzan and John Carter were semi-science fictional in nature. So, right there you have some names. Then, I read Edgar Wallace and E. Phillips Oppenheim, both sort of mystery authors.

When I opened a book in a library to see whether I would borrow it or not, if the paragraphs were too long, I didn't borrow it.

|

| Thiessen: |

This is probably something that you carried forward into your own style, then. |

| Van Vogt:

|

Pretty well. It's difficult for me to feel that a solid page without the breakups of paragraphs can be interesting. I break mine up perhaps sooner than I should in terms of the usage of the English language. |

| Thiessen: |

I read once that you felt you had to take personal responsibility for the demise of Unknown. |

| Van Vogt:

|

Well, what happened (according to my side of the story) is that John Campbell wrote me and he said, I want you to continue to do everything you're doing for Astounding, but I would like you to write three novels a year for Unknown Worlds. He said, I can get three from L. Sprague de Camp, and three from L. Ron Hubbard, and if I can get three from you, I'll take my chance on the other three from free-lance writers. It was a monthly, and he wanted a complete novel in each issue. I wrote him and said, I have a hard time with the fantasy novel, the non-science fiction novel, and I'm working on one novel which seems to be taking forever. As a matter of fact, as it turned out, it appeared in the very last issue of Unknown Worlds and it was called The Book of Ptath. It took me all that time to finish and send in. Of course, I was working on other things, but I could not seem to tie it all together, and even then it was a semi-science fictional novel.

At that time, I was really surprised, even though the war was going on, I'm surprised that there weren't enough people out there who were working on this kind of story to supply the needs of one magazine. Today, the number of writers who would be available to fill those gaps are legion.

|

| Thiessen: |

That's right. It's also true that the field has become much more popular... |

| Van Vogt:

|

Where were they in those days? There must have been their prototypes at that time who were sitting around waiting eagerly to sell stories, and yet, they were not doing that. |

| Thiessen: |

I wonder whether they were writing in other fields, or just not writing at all. |

| Van Vogt:

|

Campbell said that in a pinch, I can supply local writers here with a three page outline, and they can do the novel in three days, but I don't want those kinds of novels. He did that a couple of times at Unknown. At that point, when the real writers were not going to be able to fill the magazine, they just had to give it to a hack.

So, at that point, when I turned him down, the end of Unknown was in sight.

|

| Thiessen: |

There was quite a gap in your writing career during which time you were involved with L. Ron Hubbard and Dianetics. |

| Van Vogt:

|

Right. |

| Thiessen: |

What made you start writing again? |

| Van Vogt:

|

Well, first of all, going off with Dianetics was based upon a thought of mine. I deduced that a writer has a hot period during which he reflects the current reality of his times. There's a period when he comes up from below, from the teen period into his twenties, and if he's writing, he's already writing at that time, and he's writing about something that is real to the generation that he belongs to. I figure that that has a ten year cycle. At the end of that ten years, I began to get worried that I would run into what is known as the writer's block, the feeling of not being able to do these things. My theory was that what I had to do was make a study of human behavior. I wrote a book on hypnotism for a psychologist, and that was part of that plan, before Dianetics ever showed up on the scene. I went with him on various demonstrations, and I would be hypnotized. He taught medical doctors the use of hypnosis.

Since I was only a light trance subject, I would be his first subject so that they could all practice on me the putting on of the light trance, to which I responded in a sufficient fashion. I lived with it; I went with him on his lectures and I wrote his book. It's still selling. It's still in print.

I began to hear from Campbell and Hubbard about Dianetics. Of course, my interest was minor; it didn't strike me in any way. Then, when Dianetics was finally launched and the book was out, I received an advance copy, and then I began to receive phone calls from Mr. Hubbard, urging me to get myself involved in it because he needed somebody out here [California]. At first I told him, Ron, I'm just a writer. I was thinking, how can I convert what I've already learned into now being a writer again. But, somewhere in there, I did have the thought that this really fits in with my thinking about what I wanted to do; with what has to be done by a writer in order to stay alive as a writer.

On the seventeenth morning, when he called again (he called me seventeen mornings in a row), he made the statement that all kinds of people wanted to send money to somebody out here, and they didn't know where to send it, so I said, well, Ron, tell them to send it to me, and I'll guard it for you, and a few days later I received a letter appointing me the head of the California operation. I don't regret that at all because it was very interesting to see five hundred thousand dollars spent in a flash. I was an officer on the Board of Directors, and I was the only one that was left when everybody left the country, when we were bankrupt. My attorney and I went to all the creditors, and we were the only ones who didn't go bankrupt as a result of that. The other Foundations all went through their vast sums of money. They spent money like water, and went broke, and out of business. At that point, an oil and real estate millionaire in Wichita, Kansas, named Don [Purcell] picked up the pieces. He wrote Hubbard and Hubbard came to Wichita, and they formed the Dianetic Foundation. It was then relaunched, so to speak.

|

| Thiessen: |

So you stayed with Dianetics for about fifteen years. |

| Van Vogt:

|

Well, you see, somewhere in there, Hubbard and [Purcell] broke up; separated and that Foundation was closed down. I did not go along with the new theories that Hubbard was offering. They had a religious aspect and I paid no attention to them. |

| Thiessen: |

Scientology. |

| Van Vogt:

|

That's right. I wasn't opposed to them; it just wasn't for me. I just didn't move along that line of thinking. So, what I did, for altogether about fifteen years, it was a little less than that, really, I had a Dianetic Center where I conducted experiments with these various techniques on a total of about two thousand people, until finally I felt as if I had had my fill of human behavior — I don't mean that I was against it, don't get me wrong — it just seemed to me that I had enough systematic thoughts about what it was and what to do, except for a couple of types of cases, which I'm still following through, and some experiments which I'm conducting on myself. Other than that, I'm through with it. Also, I'm still president of the California Association of Dianetic Auditors, which is a non-Scientology organization. |

| Thiessen: |

So, after you were finished with that, you returned to writing. |

| Van Vogt:

|

No, slightly before I was finished with it, I wrote a story called "The Silkie," a novelette which later became part of The Silkie novel, and I was relaunched. |

| Thiessen: |

Okay. Are you ever going to do any sequels to some of your more popular series, like the Null-A or Weapon Shops series? |

| Van Vogt:

|

Well, Fred Pohl has suggested to me that I do a sequel to all of them. Someone wanted a sequel to Slan, and Fred Pohl wanted a sequel to the Rull stories. I have a collection coming out from DAW [now released under the title Pendulum]. It came about as follows: over the years when I was involved in Dianetics, I wrote the beginnings of many stories. I would get an idea, and then write the beginning, and then never touch it again. When I finally started to look for these stories, they were in various boxes, and were very hard to locate, but they formed the basis of some of my later novels. Also, there were a number of short stories among them, and half-written novelettes. I signed a contract with Wollheim to produce a novel called To Conquer Khyber, at least that was my title for it. [Eventually published in 1985 as To Conquer Kiber — Isaac] He says he thinks he will change it, and I gave a delivery date on it which I was unable to fulfill, so when he wrote me, saying where is that novel? I'm expecting it any hour, he said. Since I knew it was not going to be arriving any hour, first of all I put together three long novellas on a high I.Q. type thing, which he called Supermind. I said, will you accept this in lieu of the one under contract.

He said, no, we won't accept it in lieu of but we will accept it and publish it. But that held him off for six months longer on the other thing; you see, I'd also agreed to write three other novels, some of which I'd agreed to earlier. I finished two of those, one to Pocket Books and one to Doubleday.

|

| Thiessen: |

Those will be coming out soon? |

| Van Vogt:

|

Well, Pocket Books wants some slight revisions in the one that I sent them, so I don't know how soon all this will happen. |

| Thiessen: |

These are new books, not related to any of your other books. |

| Van Vogt:

|

That's right. Then (I'm coming to my point about sequels), after about six months, I got this letter from Don Wollheim, saying where is that book. So I got out a number of these short stories and novelettes that had been lying around there for so many years, and I finished enough for the equivalent of a collection. It included one called "The First Rull." When Fred said this to me, back in the mid-60's, I wrote a little bit of a story which I eventually called "The First Rull."

When I sent this collection to Don, I said will you accept this as a substitute for To Conquer Khyber, he said, no, we will not accept this as a substitute, but we will print it.

The story "The First Rull" is about 9000 words, and could serve as the first part of a new Rull novel. You see, I have in mind a title, The First and Last Rull. "The First Rull" would be like the introduction or the prolog, and then would come the main novel, The Last Rull.

|

| Thiessen: |

What about others? |

| Van Vogt:

|

I wrote the beginning of a Null-A sequel when Pohl spoke to me about it, because, you see, the original people of which Gosseyn was a descendent, or clone, came from another galaxy. They had set the situation up in such a way that they could eventually return. That's why they had the predictors, way it was set up, it's all sitting there so that when the madness blows over the other galaxy, they can all go back home. When people leave a place by force, they always plan to go back. I have a very mundane working title for this novel, called The Return of Null-A, meaning the return to where they came from. |

| Thiessen: |

Thank you. |