direct from the publisher. If you're outside of Italy, be sure to select "Estero" (meaning "abroad") under "destinazione" on the order page.

It costs €40 Euros (about $54),

which includes postage.

Guest reviewer:

Daniele Bitossi

October 1st, 2011

A Vindication of van Vogt

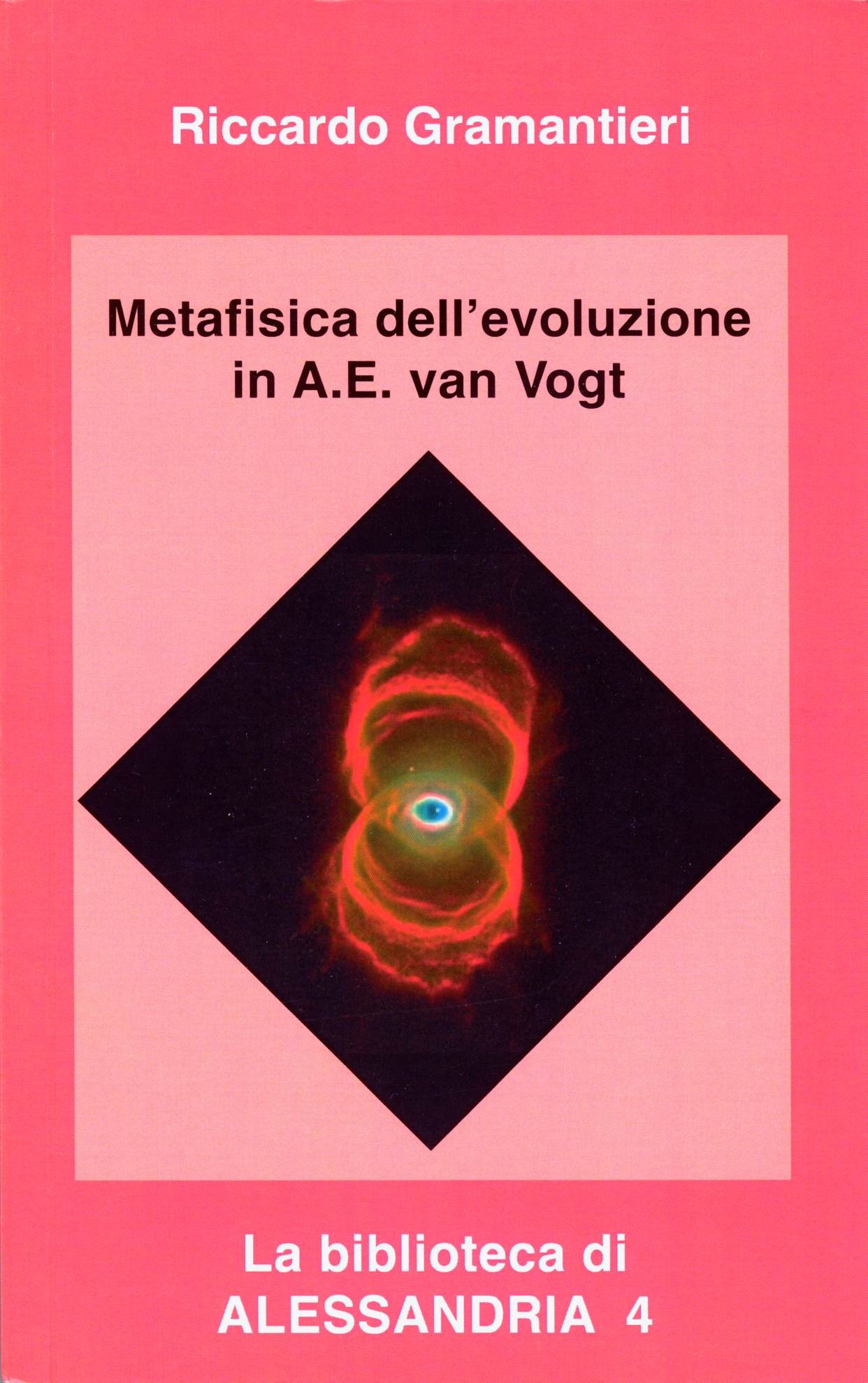

At 423 pages (the last fifty being a bibliography), Riccardo Gramantieri’s book, Metafisica dell’evoluzione in A. E. van Vogt (Metaphysics of Evolution in A. E. van Vogt) is the largest study on Van ever published in any language, and the most thorough.

As stated in the introduction, Gramantieri examines every single novel written by van Vogt. Moreover, he covers the collaborations and the sequels written by others, as well as almost all of his shorter works, with some appropriate highlights on his nonfiction. And this is not all: he speaks in detail of the relation of Van’s work to the Bates method, the General Semantics of Korzybski and the Dianetics of Ron Hubbard.

Gramantieri has read practically all of the critical essays about van Vogt, and gives some interesting speculations of his own, particularly in relating van Vogt's enthusiasm for methods of self-improvement to the polemic against academic education launched in the 1920s by H. L. Mencken.

His survey of all of Van's intellectual preoccupations, and that of his work in general, is punctilious and almost totally correct. This is for me high praise, because van Vogt’s fame in Italy is declining, together with the eclipse of science fiction as a whole.

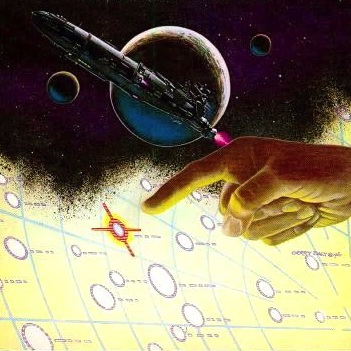

The book is divided in 14 chapters and is widely illustrated with black-and-white photos: they reproduce a lot of covers of Van’s work, and some Astounding covers. There are also some personal photos. The cover of Gramantieri’s book is included with this review.

His principal interest is centered on the novels: this is due to the Italian translations (not all of the original stories which became part of the fix-ups were translated), but Gramantieri has widely consulted the English originals, and half of the quotations in the book are in English.

This is a fundamental book for the study of van Vogt‘s work: it’s a pity the book is costly (about 50 dollars) and can be purchased only from the publisher (Elara Books of Bologna, Italy, www.elaralibri.it). So, probably, its diffusion will not be very large.

Some personal observations: Gramantieri likes some of the books from late in Van’s career which I strongly dislike, such as Quest for the Future, but this is not a defect, it’s simply a question of preference. Every reader of van Vogt has their own.

In my opinion Gramantieri is too lenient regarding L. Ron Hubbard, an evil man, as well as his methods and his religion. Van Vogt involved himself for more than a decade in Dianetics, but it remains a pseudoscientific madness.

In another part of the book, Gramantieri repeats some sentences by Sam Moskowitz (not the most accurate of biographers and critics) on Van being "a man of faith” and "a good man” (from the chapter on van Vogt in Seekers of Tomorrow, 1967, p. 87-92). These are Moskowitz’s opinions and they may be correct, but I don’t think they have the relevance Gramantieri seems to attribute to them.

More seriously, Gramantieri repeats Panshin’s point of view in Man Beyond Man, in which the critic bases the substance of his interpretation on the hypothesis that van Vogt had read and completely assimilated Science and the Modern World by A. N. Whitehead, the English mathematician and philosopher. There is absolutely no proof van Vogt ever read this work, so I think it’s rather futile to base an interpretation on this doubtful argument. The blame is on Panshin, but Gramantieri should have been a little more cautious in adopting this thesis.

Finally, I don’t think you can compare van Vogt to William Burroughs, a writer rather antipodal to Van, simply because they shared an interest in General Semantics. There are others SF writers that I think can be viewed more safely as being in Van’s orbit, such as Charles Harness and R. F. Jones, and more recently Alastair Reynolds, "the new van Vogt.”

But these are only very minor objections. This is a great book of criticism and everyone who likes van Vogt and can read Italian, must read it.