| Weinberg: |

How did you first get interested in science fiction, and in particular, how did you come to write a science fiction story? |

| Van Vogt:

|

I first read science fiction in the old British Chum annual when I was about 12 years old. Chum was a British boy's weekly which, at the end of the year was bound into a single huge book; and the following Christmas parents bought it as Christmas presents for male children. The science fiction in these stories was simple. Somebody built a spaceship in his toolshop (in his backyard) and when he left earth he took along all the neighborhood twelve-year-olds without the parents seeming to object.

Later, at age 14, I saw the November 1926 Amazing and promptly purchased it, read it avidly until Hugo Gernsbach lost control and it got awful under the next editor, T. O'Connor Sloane. So I had my background when I picked up the July, 1938 issue of Astounding and read "Who Goes There?" It was one of the great SF stories; and it stimulated me to send Campbell, the editor, a one paragraph outline of what later became "Vault of the Beast." If he hadn't answered, that would probably have been the end of my SF career. But I learned later he answered all query letters either favorably or with helpful advice. The helpful advice he gave me was to suggest that I write with a lot of atmosphere. To me that meant a lot of imagery, and verbs other than "to be" or "to have."

|

| Weinberg: |

You've stated elsewhere that "Vault of the Beast" was the first story you wrote. However, it did not appear until August 1940, long after publication of several other novelettes. How did this come about? |

| Van Vogt:

|

I think Campbell held up "Vault" because, since it had been stimulated by the reading of "Who Goes There?," there were some similarities; and he wanted a little time to go by between two stories about shape-changing creatures. |

| Weinberg: |

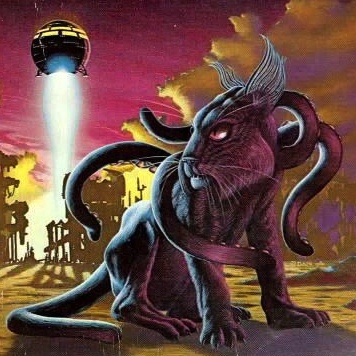

Your first published story, "Black Destroyer" was followed shortly afterward by a sequel, "Discord in Scarlet." Were you asked to write this by Campbell or did one story just follow another? |

| Van Vogt:

|

The encouragement I got from Campbell was a quick check and praise. Once the Space Beagle was launched on its mission, it seemed natural for it to breed additional thoughts. "Discord" was my idea, without special encouragement. |

| Weinberg: |

In the same vein, your first four stories published in ASF were all monster stories — i.e. the two Commander Morton stories, "Repetition" and "Vault of the Beast." Suddenly, you switched from novelettes to a novel, with no monsters and a completely different tone. How did Slan come about? And, were you worried at all at being labeled a "monster" story writer? |

| Van Vogt:

|

As you may recall, "Repetition" was already the beginning of a switch. The monster was not on the level of Coeurl and Ixtl, but more of a beast. The idea came from reading that northern trappers occasionally got a wolf by having the animal lick a sharp blade which had been suitably smeared with blood, or something. As for being worried about how readers might label me, no, it never crossed my mind. However, although it is disguised, Slan was, to me, a monster story. I consciously thought of Jommy, the super-boy and the later super-man as a variant on my monster idea. |

| Weinberg: |

During this period, both of the Morton stories and Slan were featured on the covers of Astounding. What did you think of the cover artwork used? |

| Van Vogt:

|

In those days I was new to covers; merely felt pleased that a story of mine had been honored. I later met Rogers who did some of my early covers and I was impressed with him. You have to remember that I was a bright but simple fellow from Canada who seldom, if ever, met another writer, and then only a so-called literary type that occasionally sold a story and meanwhile worked in an office for a living. As a craftsman, I made my living at writing from the moment I crossed the line at age 20, and sold my first story to True Story Magazine. |

| Weinberg: |

After what can only be described as a "meteoric" rise to the top of the SF field, you only produced two stories in 1941, both shorts. Why the sudden decline in output? 1942 had to be one of your best years as a writer. You had Recruiting Station, "Asylum," "Co-operate or Else!," "The Second Solution," "Secret Unattainable," "Not Only Dead Men" and "The Weapon Shop," all top notch stories in the year. What brought about this sudden burst of writing? |

| Van Vogt:

|

WW II began for Canada in 1939. I married E. Mayne Hull in May. By November we were in Ottawa and I was working daytimes for the Department of National Defense and writing evenings. I wrote Slan there, sent in most of it by May, 1940, and the balance shortly after. It was printed starting in the September issue. By this time I was already feeling the weight of the war in terms of extra hours that I had to work. First, a couple of evenings and then finally four evenings a week, all day Saturday, and every other Sunday. All this on a salary that never increased, and, after deductions came to $81 a month — those were the days right after the Depression. I had casually rented an apartment that cost $75 a month because I expected my writing to pay my way.

By may, 1941, I realized my doom, and I resigned — just about a month before people were frozen into their jobs. Meanwhile, the two stories I had managed to finish after Slan were printed (in 1941). But, starting in late May, I began a vigorous writing program in a cottage in the Gatineau Hills outside of Ottawa. And there I wrote all the stories that were published in 1942. It was summer. I sat on a verandah overlooking the swift Gatineau River far below, and I worked all day every day. When fall came, we moved to Toronto; and there, in a narrow hallway of a duplex I continued my writing regimen.

|

| Weinberg: |

"The Seesaw," first published in July 1941, is a pivotal story in your early career. It was the first story in the Weapon Makers series and also the first to hint at the shape of complexity to come. How much of the Weapon Makers series had you plotted when that one story appeared? |

| Van Vogt:

|

"The Seesaw" was not consciously planned to be the first of a series. Ideas came to me in the night when I would wake up, anxiously thinking about a story problem that was not resolving. Often, in the morning after several such awakenings I would suddenly have an insight of an original nature. I was — so I thought later — unnoticingly tapping my subconscious mind. Presumably, once I had the weapon shop background it was easy to jump to another idea about it as, for example, "The Weapon Shop." |

| Weinberg: |

Following up on the last question. Recruiting Station seems to signal a major advance in your career. Your early stories were filled with ideas but seem to be lacking in characters (other than perhaps the well-detailed monsters). Most of the people in the stories are no more than pulp standards — the heroine of "Vault of the Beast" being a perfect example. However, to some extent in "The Seesaw" and then full force in Recruiting Station your characters develop character. You seem to be striving for realistic characters in unrealistic (unbelievable) situations. Was this an intentional shift or just your maturing as a writer? |

| Van Vogt:

|

Recruiting Station was a story that came as the result of many anxious awakenings during many nights. So much so that, later, in 1943 — in Toronto — I suddenly noticed the process. And that night I took an alarm clock, moved into the second bedroom; and that night I awakened myself every 1 & 1/2 hours, thought about my story problem, and went back to sleep. I'm sure that this enriched many of my stories with unusual new ideas. |

| Weinberg: |

Following up on Recruiting Station. This has to be a perfect example of the type of story you are most famous for — the extremely complex "wheels-within-wheels" construction. Do you feel that you were a "pioneer" so-to-speak in bringing this type of story into the pulp SF field? |

| Van Vogt:

|

I don't recall having any self-awareness about the intricacy of my stories. I wrote what interested me; and my method of working out my story through the dream process probably underlay the wheels within wheels aspect. I was merely pleased with some of the ideas — but never thought of them as especially intricate. |

| Weinberg: |

Recruiting Station raises another interesting point that is reflected in many of your stories and one that I'm surprised has never been noted before. Women play a major role in many of your stories — intelligent, competent women, who are often the focal points of the story. Norma Matheson in Recruiting Station, the Isher Empress in the Weapon Shop series, Patricia Hardie in the Null-A series, and others. Did you make a conscious effort to break the pulp stereotypes of women that had been used before you? And, again, do you feel this use of important women characters was an attempt to escape the traditional pulp molds of science fiction? |

| Van Vogt:

|

The presence of women was influenced by Mayne. She read science fiction to see what it was; and of course, she read all my stories. And she was an early supporter of women's rights — I even went to some meetings with her before we got married. She pointed out the male stereotype you mention; and I thought about it, and it seemed fitting and proper that something be done about it. |

| Weinberg: |

"Co-operate or Else!" and "The Second Solution" both were Ezwal stories and in a sense seemed to signal a brief return to the monster genre. Were these meant to be a series of their own or were they intended to be part of a larger grouping (as they later did end up as part of the Rull series)? |

| Van Vogt:

|

Neither story had any original connection with the Rull stories. In my usual fashion of working on one idea, and then later seeing another possibility in that idea, my stories accumulated on me without having any basic, or planned, order. But no doubt on the subconscious level relationships were presently noted. |

| Weinberg: |

"Secret Unattainable" was a switch — from complex SF of the future to World War II Germany. What was the background to this story? |

| Van Vogt:

|

"Secret" was written in Toronto, and was the result of my daily reading in the Toronto Globe a daily report by a man who seemed to understand, or have enormous knowledge, of both the German and allied part of the war. There was so much detailed information that one day I woke up and had the thought. That was the beginning of "Secret," but of course I then got Hitler's autobiography from the library, Mein Kampf, and other related material. |

| Weinberg: |

"The Weapon Shop" was followed quickly by another story in the same series The Weapon Makers early in 1943. This question can probably be extended to any of your series stories. How much planning do you do in advance towards the entire series — in other words, do you have a definite plan in mind that will take several stories to complete, or is each story composed and prepared separately. Was the "Weapon Shop" series originally planned as a series, or did it grow one story at a time? |

| Van Vogt:

|

The Weapon series grew one story at a time; and as you may be aware the development of The Weapon Makers in its magazine form paralleled Slan in that there were two viewpoints — apparently, I had no other way of writing a novel except to repeat what I had already been successful at. I seem to remember that Campbell was not too happy with the two viewpoints. However, after it was published he wrote that one of the heads of Street and Smith, the publishers, had chosen the three issues containing this serial to see what was going on in Astounding; and that he commented very favorably on the story. |

| Weinberg: |

In 1943, you had two short novels "The Great Engine" and "The Beast" which together actually formed one longer piece. Were these conceived (or even written) as a novel or were they done as they appeared? |

| Van Vogt:

|

"Engine" was one idea; and "Beast," and subsequently The Changeling, were written without any subsequent joining in mind. |

| Weinberg: |

Again, the Dellian Supermen stories which were published in book form as The Mixed Men appeared as three stories from 1943 to 1945. Were these all written at the same time, or planned at the same time, or just done separately? |

| Van Vogt:

|

Separately. |

| Weinberg: |

In the Nicholls Encyclopedia of SF they use the term "fix-up" in which a writer takes several of his stories, often unconnected, and rewrites them into a novel. They give you credit for the idea and denote you as master of the genre. In writing many of your stories during this period, did you have any idea that you would use them as parts of novels years later? |

| Van Vogt:

|

Starting as a 20-year-old I learned slowly about the writing business and about publishers. All those early stories were bought outright — all rights — many of them for 1 cent a word — because no one in those days thought of the subsequent book and paperback market. In 1950, when Horace Gold was first editor of Galaxy, he bought only serial rights. Naturally, writers flocked to this favorable market — and I received a letter from Campbell stating that Street and Smith would release all except serial rights to my stories on request. I put in the request at once.

Fortunately, it was possible for me to do this because Campbell's letter came to me at an address that he had. Several other writers, who had moved — and stopped writing — did not receive the letter. Hence, they did not write to ask for their rights, and did not get them. So that when Condé Nast bought out Street and Smith, it was too late to recover rights — so these authors discovered after they belatedly found out what had happened. Now — as a consequence I had all my best stories on hand. And occasionally someone would write and ask for a shorter length story for an anthology. But, starting in 1948, I was given special permission to have World of Null-A published by Simon and Schuster — Street and Smith's secretary wrote me a personal letter saying that under special circumstances they would release such rights, on request.

In the early fifties the paperback publishing business began; and they wanted novels primarily. And so I began to look over my work to see what I could fit together. It was strictly commercial. The pay was low, but it was pay. The contracts were awful; but slowly I learned what to sign and what not to sign. Let's put it very simply: a novel would sell whereas the individual stories seldom did. Hence, the great thought came; and the fix-up novels began. It was a strictly commercial idea in a period when incomes were tiny, and pulp writers all across the land were starving. It was only later that I learned the fix-ups had their critics. I could only shake my head over these people; to me, they were obviously dilettantes who didn't understand the economics of writing science fiction.

|

| Weinberg: |

The World of Null-A which appeared in Astounding in 1945 still has to be your most famous story. Also your most criticized. Do you feel that most of the criticism, aimed primarily at the use of Null-A logic as well as the complexity of the story itself was justified? |

| Van Vogt:

|

I was fascinated by General Semantics; and, as far as I was concerned, I dramatized its main points within the frame of my dream development of story ideas in it. For example, the death of Gosseyn at the end Installment One of the serialized version was designed to dramatize that no two objects in the universe are alike — although when he appears again at the beginning of Installment Two it looks as if maybe they are. Etc. |

| Weinberg: |

Null-A presents a world of the future completely divorced from our own. This is the case in the Weapon Shops series as well. The entire system of government is different but the social structure of society seems to be the same. Do you feel that your futures were really much different than our society other than for the major structures of the government on which you focused? |

| Van Vogt:

|

By my view SF writers have from the beginning explored options. In the Null-A stories my question was, can man be improved by a system of mental training? Improved, that is, so that he can live without police, without government, and without any technology to keep him that way by the method I used in, for example, The Anarchistic Colossus. In the Weapon Shop series I assumed that man's basic nature was unchangeable. So I devised a permanent party in power: the imperial house of Isher, and a permanent opposition: the weapon makers. From an indestructible weapon shop an aggrieved citizen could buy a defensive weapon, whereby he could defend himself from an attack. In The Anarchistic Colossus, freedom from government and police was maintained by a computer system that permitted no double parking, no harassing, no mugging — you name the typical basic human offense; if you did it, you got yours right there. |

| Weinberg: |

Again, on planning for the future. The Pawns of Null-A helped explain many of the loose ends left by World though it raised as many questions as it settled. However, on viewing the two stories as a whole, one has to be struck by the way many of the unanswered questions raised in the first story are logically solved in the second, making many of the loose ends of World perfectly logical. Did you have any thought of the sequel while working on the first story? And, more to the point, were many of the loose ends left in the first story resolved already if not on paper at least in thought when the first story appeared? |

| Van Vogt:

|

Yes, they were resolved in thought — although at the time I had no intention of writing another novel; that came later. The reason they were resolved in thought is because, essentially, the principal problem of Players was already on stage in World: that is, the attack by entities of the Greatest Empire. When Fred Pohl was editor of Galaxy, he urged me to write a third Null-A novel; and I actually started it — and will finish it one of these days. The "loose ends" of Players imply what the third novel should be about. I have found, in writing a novel, that when I'm about halfway through, if I go back and examine the implications of the first 10,000 words, the necessary ending is right there. Basically, the necessary wind-up of the Null-A stories is in World and Players. |

| Weinberg: |

Clane Linn has to be one of your most interesting characters. Again, as he was the hero of a series of stories, was the entire series plotted before the first story appeared, or was it a group of stories that grew as each one was being written? The Empire of the Atom stories always seem to be compared to I, Claudius by Robert Graves, even to the cast of major characters in the Linn family. Was the Graves book an influence on your work? |

| Van Vogt:

|

When I came to Hollywood, I met a number of screenplay writers. And so I discovered that "original" screenplays were actually parallels of published novels. Later, when television came into full power, paralleling was a way of life. Probably, all the stories of history have been taken by a TV writer and brought up to date in some way, and paralleled on the story line. Still later, I discovered that some university writing courses teach paralleling.

Anyway, when I learned of it, I was reminded that Slan was a paralleling of Ernest Thomson Seton's The Biography of a Grizzly: the pattern of Grizzly was: his mother is killed at the beginning, and the cub is on his own. He doesn't find an old lady to help him, but he manages to find a place where he can hide for his first year or so. By then he is the equivalent of Jommy at nine — stronger than all the lesser animals of the forest; but he'd better stay away from full-grown black bears, etc. Finally, he comes to what Seton called in his heading: "The Days of His Strength." He is a full-grown grizzly bear, king of the forest and mountains. For the most part I didn't need parallels like that, but that one struck me as being interesting, and I used it automatically. The reason I didn't need such things is that I know story structure, and how it should go — within my frame, that is.

Anyway, the early period of the Caesars in ancient Rome has always been, along with the Florentine Medici family period of Italian history, among the two most interesting times of our past. I read extensively in both periods, and know them well. So when I read Graves novel I did not immediately think of how-could-Ancient-Rome-with-a-mix-of-Middle-Ages-Florence be futurized, but when I did it was at the height of my discovery of the paralleling that is the meat of Hollywood writing; so it was automatically a good idea to parallel I, Claudius.

Subsequently, James Blish wrote a very severe criticism of the work. I was a little amazed, and, in fact, he showed no such outrage when John Brunner utilized a John Dos Passos story pattern in Stand on Zanzibar and other writers took dozens of famous stories, including Shakespeare's plays as their patterns. But nonetheless that was the end of my own paralleling career. Damon Knight, a friend of Blish, praised Empire though he was critical of most of my other work.

|

| Weinberg: |

Isaac Asimov recently stated that he thought you and Robert Heinlein were the two authors John W. Campbell admired most during the 1940s. Did you have much to do with Campbell as an editor and did he influence your writings? |

| Van Vogt:

|

About mid-1941 Campbell wrote me that I had shown the same ability as Heinlein to produce outstanding science fiction, and therefore he asked me to produce for him as much as $300 worth of stories a month — meaning that any story of mine and, presumably, Heinlein's would take precedence over the work of stories submitted by other authors. I didn't think of it in those terms at that time; but that's when I was up in the Gatineau north of Ottawa writing for one cent a word at a time when government salaries were $81 a month. It was Heinlein he mentioned; so presumably Heinlein and I were his favorite authors for a period at that time. Heinlein, as you probably know, went on to much greater book and paperback success than I ever did; but I cannot complain: my readers kept me going also. |

| Weinberg: |

On the same note, Campbell was noted for feeding his writers ideas. Did he give you any ideas that developed into stories that were published in ASF? |

| Van Vogt:

|

Campbell offered me an occasional idea. But the fact is that it takes me a long time to organize someone else's story thought into my own system. He suggested the concept of a wizened old witch, which I eventually evolved into "The Witch" for Unknown Worlds. What I principally utilized Campbell for was information. When I was writing "The Storm" I wrote him and asked him if there was a possibility that some equivalent of a storm could exist in space. He wrote R.S. Richardson, and the result was what appears in the story. Campbell wrote me long letters loaded with information whenever I queried him, or if he had some thought stimulated by a story of mine.

Apparently, he kept no copies because, as it turns out, when Perry Chapdelaine — who will publish Campbell's letters in conjunction with George Hay, of England — contacted Condé Naste, no copies were found prior to 1951. However, I have furnished Perry with copies of all the correspondence; and it was so voluminous — each letter being about 4 pages, single space — that I didn't even take the time to reread them. So I'll have to do that one of these days in case there is anything personal in them that should not be printed for one reason or another.

|

| Weinberg: |

On looking back on the period from 1939-1950 when your work appeared in ASF, what story is your personal favorite of all the ones published? And, in a different vein, is there any story you wish you had written different, or perhaps not at all? |

| Van Vogt:

|

I keep saying that my personal favorite is The World of Null-A, and I seem to have convinced myself. Of my short stories I think I prefer "The Monster" (aka "Resurrection"). The SFWA voted the novelette, "The Weapon Shop" my best shorter length story.

My fix-up novels are:

Total of 10.

And I novelized — that is, lengthened or expanded — Mayne's Artur Blord stories and her short novel, titled as follows:

Out of all of these I wouldn't be surprised if the total income did not amount to a couple of hundred thousand dollars, compared to the few thousand they might have earned from anthologists as separate stories.

When I consider the alternative in a field where I have always considered myself a craftsman and not as an artist, I have not a single regret. Every story I wrote was interesting to me at the time, for reason that psychologists might be able to explain but I'm not even trying.

|